The diversion of public highways, and particularly public paths, is commonplace. Path diversions are generally made by administrative order under s.119 of the Highways Act 1980, or s.257 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990: the procedure is relatively inexpensive, and usually successful (if success is equated with the order being confirmed). Even before s.42 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 first conferred such administrative powers on highway authorities, it had always been possible to divert a highway (of any description) by an order of the magistrates’ court (and still is, under s.116 of the Highways Act 1980). So it is that many highways which exist today have been diverted at some point in their history. Sometimes, that diversion may have taken place so long ago that no record exists of the diversion, and no available map is sufficiently old to show its former alignment (but perhaps a slightly sunken track by an old hedgerow may suggest the original way today). More often, in relation to public paths, the highway authority will have diverted the way after the definitive map and statement was drawn up in the 1950s.

But what if a path, recorded on the definitive map as a public footpath, and diverted under s.119 of the 1980 Act, turns out after the event to host ‘higher’ rights than those recorded? What is the effect of the order on those rights which were latent at the time of the order, but unrecognised?

Surprising to report, there seems to be no authority on the question. In Brand & Brand v Philip Lund (Consultants) Ltd, an action which successfully proved (at least between the parties) that Ramscote Lane in the Chilterns was a public carriageway, HH Judge Paul Baker QC notes that:

‘an order was made diverting the track so that it now runs round the edge of the wood. The order was made under the Highways Act 1959 section 111, which is now the Highways Act 1980 section 119. …By adopting the plan in the statement of claim, Lund Consultants appear to accept the efficacy of this order as regards the route of any vehicular way it may be able to establish. I have had no argument on that particular point.’

At that time, s.119 conferred powers to divert only a footpath or a bridleway, and indeed, the order made by the council referred to a bridleway. However, in discussion between the bench and counsel after judgment was handed down, it was realised that, if an order was to be made declaring a vehicular right of way along Ramscote Lane, it was necessary to decide whether the right of way existed along the original way, or the replacement way following the diversion. The judge concludes that:

‘the common-sense of this is that, once there has been a diversion, whatever rights there were over the road are diverted. Just a quick look at the relevant section of the Highways Act would seem to show nothing that precluded that view.’

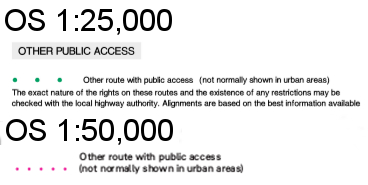

It seems that counsel for Lund was denied an opportunity to make further representations on that point later at a resumed hearing later in the day, but as his client got his declaration of a vehicular right of way over the replacement way, he might not have been too disappointed about that (although the width of it was tight: 6ft at one point). So the vires of the diversion order was not seriously challenged by any of the parties. Which is a pity. For, so far as I am aware, this is the only reported case even to touch on the question. In due course, following the trial, the ‘bridleway’ became shown on the definitive map as a byway open to all traffic throughout: you can see here where the byway now follows the edge of the wood where it formerly passed through adjacent fields.

|

| Public footpath along Tenchleys Lane, near Limpsfield Chart, Surrey. |

The public footpath formerly followed the course of the Lane through the gate to left and through the garden of Tenchleys Barn. Following a recent diversion, it now follows what, at the time this photograph was taken, was marked as an ‘alternative path’. What if Tenchleys Lane were now proven to be a bridleway? In fact, an attempt to demonstrate just that failed in 2015 (see Pannageman’s report).

For any way with unrecorded higher rights diverted by order so as to expressly address only the recorded rights, there must be at least five conceivable outcomes (in this exploration, I refer to the original way as such, and the diverted way as the replacement way):

- The order is effective, and unrecorded rights are lost. The order stops up the original way (of whatever status), and creates the replacement way of the status set out in the order.

- The order is effective, and the replacement way is of the status of the unrecorded rights. The order stops up the original way (of whatever status), and creates the replacement way of the same status commensurate with the unrecorded rights formerly embodied in the original way.

- The order is effective, but unrecorded rights are preserved. The order stops up the original way only so far as provided in the order, but the higher unrecorded rights are retained along the original way. The order creates the replacement way of the status set out in the order.

- The order is effective, but only so as to create the replacement way. The order does not stop up the original way, and creates the replacement way of the status set out in the order.

- The order is ineffective. The original way continues to subsist, and the replacement way has no legal status (unless, perhaps, it has been in use for so long that it is deemed to have been dedicated).

None of these options is a particularly attractive one to apply to every possible case, which is why it is hard to formulate principles which can be universally applied. That is not to say that a court should or would adopt principles tailored to the particular circumstances — it ought to be possible to discern some general principles which would apply in every like case. But the approach which a court might apply in a case which comes before it might well be influenced by the circumstances — even though the legal principles, enunciated in that case, but applied in a similar case with different circumstances, might produce unfortunate results.

Let’s illustrate these circumstances with three examples, each of which contemplates the diversion of a footpath subsequently discovered, thanks to historic evidence, to be (or at least, to have been) a bridleway. First, consider a way which is diverted out of a cross-field alignment so that the replacement way runs along the farm drive. In these circumstances, there is no practical reason why the replacement way, a farm drive, should not serve as a bridleway instead of a footpath.

What if the original footpath were diverted to pass through a new housing estate, so that the replacement way were designated with a width of one metre, and were enclosed by two metre high panel fencing on both sides? In these circumstances, the redesignation of the replacement way as a bridleway would be highly unsatisfactory, being of insufficient width to pass two horses. Yet the original way might now be lost under the housing development, and incapable of being resurrected. Practicality (from the landowner’s perspective) desires that the higher, bridleway, rights, should have been extinguished without replacement.

For our third example, imagine a footpath which is diverted out of a farm yard and onto an elaborate detour around the farm buildings, on a narrow alignment with a width of less than one metre, and several stiled crossings of farm access routes. As in the second example, the replacement way is entirely unsuited to use as a bridleway: it is indeed physically impossible to use it as such, and there is no warrant to dismantle the stiles which are lawfully set out as limitations in the diversion order. But, much as the farmer might regret the resurrection of the original way through the farm yard, it is still physically practicable to pass that way, even if it is not particularly welcome to the farmer.

So a court could hardly help but be influenced by the circumstances of a case which comes before it. What of the legal principles which it should apply?

In every case, an order has been made that purports to divert a way which is not as it is described. That constitutes one inevitable defect in the order, which is a failure of description, but there is a second possible defect, which is an absence of powers. If a public path diversion order is made by a local authority under s.119 of the Highways Act 1980, the authority has a power to divert by order any public footpath, bridleway or restricted byway (the last owing to amendment of s.119 by SI 2006/1177, r.2 and the Schedule) in accordance with the requirements of the 1980 Act. What if the original way turns out to have been a carriageway over which rights for mechanically propelled vehicles endure (in effect, what might properly be recorded as a byway open to all traffic)? The authority has no power to divert such a carriageway. The order may have been duly advertised, processed and confirmed, but it remains that the order purports to do what the authority has no power to do. Will a court, advised of the error long after the date of confirmation, leave such an order undisturbed notwithstanding that it was, and remains, blatantly ultra vires? In R (Andrews) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (generally referred to as Andrews 1), the High Court was eager to rescind an unlawful award of a public path in an inclosure award made nearly two centuries earlier, on the ground that the inclosure commissioners had no power to make the award. That decision was subsequently overturned, over twenty years later, in Andrews 2 (see Pannageman’s final comment on the case), but only on the ground that the commissioners did have the necessary powers: the Court of Appeal left undisturbed the finding of the original court that it was proper to revisit the question of powers after such a long elapse of time. Would an ultra vires public path order be equally vulnerable to rescission? Para.4 of Sch.2 to the 1980 Act (applied by para.5 of Sch.6) provides that, after the expiry of the six week period for statutory challenge, an order may not, ‘be questioned in any legal proceedings whatever’ — but there was a similar ouster clause in Andrews 1. It must be said that the question of the ultra vires exercise of powers by public bodies could, and does, fill a substantial part of a legal text book, Andrews 1 cannot be considered, by a long way, the final word on the subject, and I do not intend to explore the point further here. But it is a vexed question surely because, whatever the circumstances, it is unattractive to apply the same rules in every one of a substantial number of highly diverse cases.

Usually, however, a public path diversion order will not have purported to extinguish rights for mechanically propelled vehicles. Far more likely is that the rights addressed in the order are within the scope of s.119 (i.e. the original footpath is subsequently discovered to be a historic bridleway or restricted byway, or the original bridleway is subsequently discovered to be a historic restricted byway), but the order is defective in adverting to the original way as only a footpath or bridleway (as the case may be). In such a case, the order is defective, in that it purports to extinguish something inferior to the true status of the original way, and to set out a new way which is equally inferior. But this time, there is no doubt that the authority had a power to divert the way according to its proper status, even though it did not properly exercise the powers, nor invite objections on that basis. And while the order is defective, the legislation seems to make the position clear: s.119(1)(b) provides that the council may, by order, ‘extinguish, as from such date as may be specified…, the public right of way over so much of the path or way as appears to the council requisite as aforesaid.’ This provision does not provide for the extinguishment of whatever is specified in the order (be it a footpath, bridleway or restricted byway), but the extinguishment of the ‘public right of way’. A court might find the comprehensive scope of that provision seductive in determining the effect of the order on previously undiscovered higher rights.

But there is no compensating solace in s.119(1)(a). This enables the council, by order, to ‘create, as from such date as may be specified in the order, any such new footpath or bridleway as appears to the council requisite for effecting the diversion’. There is no flex in those words to infer that, despite the authority’s error in specifying the creation of a footpath, the legislation has actually operated to create a bridleway (or a restricted byway, as the case may be). My belief, albeit on fairly meagre provision, and in the absence of a compelling set of practical considerations to direct the court to a different conclusion, is that, provided that the order could lawfully stop up the original way, it will be taken to have done so — and that the replacement way will be precisely as specified in the order, and no more.

Of course, different legal mechanisms may lead to different outcomes. If the way was diverted by order of the magistrates’ court under s.116 of the 1980 Act, the magistrates had undoubted power to divert and stop up any highway, and I would conclude that, even if the original way was described only as a footpath or bridleway, but was subsequently established to be a carriageway for all vehicles, the order will be taken to be effective in the terms described in the order.

But that is to decide only between the first two of the conceivable alternatives set out earlier in this blog. What of the other three? In my view, they are conceivable alternatives — but barely so. Alternative three contemplates the designation of the original way as a class of highway unknown to the common law: a bridleway over which there exist no rights on foot, or a restricted byway over which there exist no rights on foot, and perhaps no rights on horseback or on cycle (depending on the terms of the diversion order). Such highways are not entirely alien: motorways and some roads subject to traffic regulations orders are prohibited to ‘inferior’ classes of traffic — but these highways have been so designated for coherent reasons. I find it impossible to imagine how a bridleway available to horse riders but unavailable to pedestrians could make sense. If, however, one conceives that the original way endures without any restriction on the classes of traffic which may use it, then that is alternative four… .

Alternative four is superficially more attractive from a public interest perspective: the original way is found to endure, as does the replacement way. But it has little support from the legislation, nor from logic. The landowner will suffer a ‘triple whammy’: once the error has been identified, not only is the original way resurrected long after it was purported to be extinguished by order, but it is now found to carry higher rights than previously manifest — and the landowner is also lumbered by the replacement way too (it will be small solace that the replacement way has only the status set out in the order).

Alternative five might be equally acceptable to the public: the order is deemed to be of no effect whatsoever. Given that the order was defective (we assume here it was not wholly ultra vires), that might not seem unreasonable — but flaws in the procedural process do not necessarily void the action taken by a public body. And in terms of practical realities, it is perhaps the outcome least likely to make sense, in that the original way may long since have been developed on the assumption that it has ceased to exist, and the public will have used the replacement way as if they had a right to do so. Indeed, throwing open the replacement way for public use might be taken to amount to common law dedication of a right of way, were it not that in the ordinary course of events, the order expressly creates the right of way. In Powell and Irani v the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and Doncaster Borough Council (reported by Pannageman), the court found that a way which had been used by the public long after it had been diverted elsewhere, had come into being through presumed dedication, even though the landowner might have assumed he had no power to interfere with use of the way because it was still shown incorrectly on its original alignment on the definitive map. So alternative five might, in many cases, be indistinguishable from alternative four: both may lead, after a sufficiently long interval, to the establishment of public rights over both the original and replacement ways.

If this analysis turns out to be correct, it has significant implications for research to identify and record, on the definitive map and statement, under-recorded rights of way. For if the candidate right of way was previously diverted with only the status then apparent, it may be that any application to ‘upgrade’ the way cannot succeed, at least in respect of the original way stopped up. Given how widespread is the diversion of public rights of way, this may be a significant impediment to such research.