A. Introduction

A.1. ‘Path extinguishment day’ is set for 1 January 2031. That’s the date on which the provisions to extinguish unrecorded historical (i.e. pre-1949) rights of way take effect. The provisions are contained in Part II of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (hereafter, the 2000 Act). Section 56(1) provides (following amendment by r.2 of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (Substitution of Cut-off Date Relating to Rights of Way) (England) Regulations 2023 (SI 2023/1126)) for that date to be set back to 2031 from New Year 2026.

A.2. Section 53 of the 2000 Act defines what, in general terms, is extinguished. The key effect (in subs.(1)) is to extinguish a highway which was a footpath or bridleway before 1 January 1949, which continues to be a footpath or bridleway in 2031, and which is unrecorded. Unrecorded means that the highway is not recorded in a definitive map and statement.

A.3. It’s worth pausing here to note what is omitted from the legislation but frequently not understood: in general terms, historical public roads are not extinguished, whether recorded or not. If a way was a public cart road in 1949, then it endures the 2031 extinguishment, even if not shown on the definitive map and statement. That perhaps primarily is because, were it otherwise, a majority of public roads would be at risk of extinguishment. But it also promotes the curious likelihood that landowners, faced with claims after 2031 to record historical rights of way on the definitive map and statement, will seek to produce evidence (perhaps from hitherto undisclosed archives) that what is claimed as a public road was actually (in pre-1949 history) a footpath or bridleway by reputation, and therefore extinguished in 2031 under s.53. Of course, their incentive is to flourish those records only after 2031, when the evidence they contain is no longer of any use to those claiming footpaths or bridleways.

A.4. However, subs.(3) articulates a further extinguishing provision. Briefly, a highway which is recorded in the definitive map and statement as of a particular status will have any unrecorded pre-1949 higher rights extinguished — but leaving the recorded status intact. Thus (see subs.(4)):

- any rights to ride (a horse or cycle), drive animals, or to drive a vehicle, over a footpath;

- any rights to drive vehicles over a bridleway;

- any rights to drive mechanically-propelled vehicles over a restricted byway.

A.5. For example, if an old green lane, set out in a nineteenth century inclosure award as a public carriage road, is recorded in the definitive map and statement as a footpath, then all rights to ride or drive along it will be extinguished in 2031 — notwithstanding that it is a historical public road and would not be extinguished if it were not shown in the definitive map and statement at all. It seems it is better for a road not to have been recorded at all, than for it to have been recorded erroneously.

A.6. There is a power, in s.54(1)(d) and (5)(c) and s.56(2)(b), for the Secretary of State to prescribe, in regulations, exceptions to extinguishment. It is widely expected that regulations will be made, in the next few years (and in any event before end 2030), to address exceptions in two key categories:

- highways which are entered in a list of publicly-maintainable streets held under s.36(6) of the Highways Act 1980 (hereafter, the 1980 Act);

- highways which are the subject of undetermined pre-2031 applications to make a definitive map modification order, or such orders which themselves remain undetermined by 2031.

A.7. Both these exceptions were the subject of an assurance informally issued by Defra in October 2023. It is surprising that these exceptions were not specified in the 2000 Act, although there is a strong hint in s.56(2)(b) that regulations should be made in relation to the latter.

A.8. Defra also at that time said that highways in urban areas would be excepted in regulations, but the details of how an urban highway would be identified, and what provision would be made for trans-boundary highways (part in and part out) were not only not clarified, but are not currently the subject of any consensus.

A.9. Defra added that the Secretary of State had decided not to prescribe an exception for pre-1949 highways in continuing regular use. Such an exception was recommended by the Stakeholder Working Group on rights of way (albeit the definition of such ways had not been addressed), and widely expected and relied upon by stakeholders generally. As the decision is likely to have a very substantial practical effect in extinguishing footpaths, and bridleways, which, although not recorded, remain in regular use to this day, a reversal of the decision between now and 2031 cannot be ruled out.

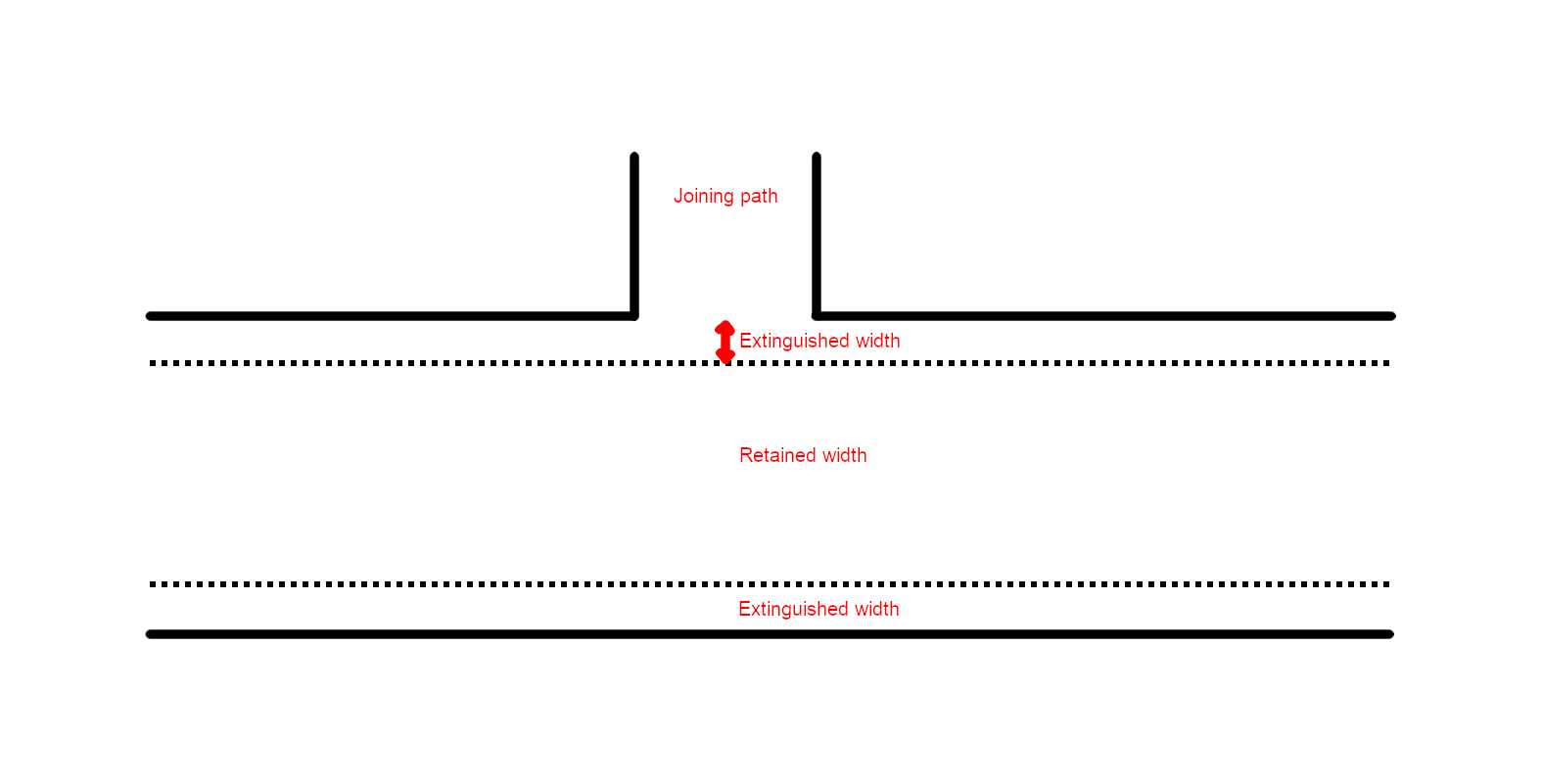

A.10. Defra further said that it had not come to any conclusion on whether any unrecorded width of a highway otherwise recorded in the definitive statement should be extinguished. You can see further discussion of this issue in my blog, Extinguishing effect on widths of paths under Part II of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000.

A.11. Notwithstanding that the 2000 Act does not directly set out exceptions in what appear to be the most high-profile cases, s.54 nevertheless does include a number of express exceptions. Some of them are quite surprising in their unexpected and potentially radical effect.

A.12. Unfortunately, s.54 is a remarkably impenetrable piece of drafting. What does it do? I have sought to explain the exceptions below. I address them, broadly speaking, in the order in which they appear in s.54, not in terms of their importance.

A.13. Bear in mind that these exceptions are relevant only if the excepted highway is not recorded on the definitive map and statement on path extinguishment day. And bear in mind too that the extinguishing effect of s.53 applies only to ways which are pre-1949 in origin. None of these exceptions is of any use if there is insufficient evidence that the way is indeed a highway: it is not enough to show that a way is excepted from extinguishment — one also must prove, on the balance of probabilities, that it is a highway.

A.14. Examples are illustrated by ways already recorded on the definitive map and statement because they are easy to identify: clearly, such ways are not generally at risk and therefore will not in practice benefit from the exception, save in relation to the extinguishment of unrecorded higher rights.

A.15. What follows is my personal opinion. I am not a lawyer: if you need legal advice, you should seek it. But if you see something which you think is wrong, please comment, and I will take another look.

B. Inner London

B.1. It is a highway in the former administrative county of London, including any continuation of the same path outside that area.

B.2. The former administrative county of London is what is now known as inner London, and prior to the reform of London government in 1965, was the area of the county of London (save that North Woolwich, formerly within the county of London, is not within inner London). In short, path extinguishment day does not operate in inner London and North Woolwich.

B.3. This applies too to any right of way over a highway in inner London. So, for example, restricted byway rights over a way recorded as a footpath on the definitive map and statement for an inner London borough are excepted from extinguishment.

See subs.1(b) and 5(b).

C. Wet-weather paths

C.1. It is a footpath or bridleway which runs alongside a road, not being part of that road.

C.2. This isn’t about pavements (which usually are part of the same highway). Chiefly, it’s about ‘wet-weather paths’, which form on the other side of the hedge, wall or fence bounding a road, and traditionally were established to enable pedestrians (invariably — seldom horse riders) to escape the mud, dirt and traffic in the road, and walk alongside the road in the field. Many of these wet weather paths are recorded on the definitive map and statement, but many more are not and often can be identified on older Ordnance Survey County Series maps. Indeed, it’s not unusual to find both the green lane and the wet-weather path adjacent are unrecorded, or that only the green lane is recorded but as a footpath, or even that the green lane is unrecorded and only the wet-weather path is recorded.

C.3. Similar adjacent paths can be found in other circumstances: for example, where a ‘pavement’ has been created inside an adjoining field (but this usually will be post-1949 in origin); where the road follows a watercourse, or regularly is flooded; or where the road passes through a ford and an alternative but nearly-adjacent route is provided for pedestrians.

C.4. Some roads have pavements or footways which become separated from the carriageway, either by being raised up on causeways or above any cutting through which the carriageway passes, or by briefly becoming separated from the carriageway (perhaps taking a shorter route around a bend). If these ways are part of the same highway, they will be unaffected anyway; if they technically are separate from the carriageway, they should be preserved by the exception.

C.5. It is not only the footpath or bridleway which runs alongside a road which is excepted, but a continuation of the same footpath or bridleway to connect with another highway (which is not itself extinguished). For example, a footpath which leaves and then initially runs alongside a road, cuts off a double bend in the road, and rejoins the road further on, will be excepted. So will a footpath which leaves and then initially runs alongside a road, before heading off to join another road, or another footpath. All that is required for the exception to apply is that there is some part of the footpath or bridleway at the side of a road.

C.6. What sometimes can happen is that a footpath leaves and then initially runs alongside a road, then has a connection back to the road at the point where it strikes out across the fields to another highway (for the use of those who wanted to pick up the footpath from further down the road). It seems that the continuation of the same footpath beyond the connection back to the road is not excepted. That is because subs.(3)(a) excepts only a footpath which extends from the excepted part (i.e. adjacent to the road) ‘to, but not beyond, a retained highway’. Because the excepted part itself connects with a retained highway at both ends, i.e. at the start, and at the connection back to the road, nothing beyond it is excepted. In practice, it may well be difficult to determine from historical records whether there was such a connection back to the road.

C.7. It is not unusual to find a green lane, which itself is an unrecorded public road, which also benefits from an adjacent, unrecorded, wet weather path. Neither the green lane nor the wet weather path will be extinguished: the green lane because it is a public carriageway, and the wet weather path because it is at the side of a road.

Photo © Robin Webster (cc-by-sa/2.0)

C.8. This example at Ride Lane, Farley Green, Surrey, shows a wet weather path on the east side of an old holloway.

C.9. Would this bridleway at Beech Lane, Effingham, Surrey, be excepted although it is displaced from the carriageway by up to 20 metres? As at least part of it is truly at the side of the carriageway, it appears the answer is yes.

See subs.(1)(c)(i), (3)(a)(ii), (3)(b) and (4).

D. Inter-carriageway paths

D.1. It is a footpath or bridleway which runs between two separate strands of the same carriageway.

D.2. Some dual carriageways divide into two separate strands separated by more than a central reservation: this can happen where road improvements were carried out in the twentieth century so that one carriageway (in one direction) retained the original alignment, and a new carriageway (in the opposing direction) took an improved and separate alignment. A footpath or bridleway connecting the two is excepted.

D.3. It is not only the footpath or bridleway which runs between the two strands of the same carriageway which is excepted, but a continuation of the same footpath or bridleway to connect with another highway (which is not itself extinguished). For example, a footpath which starts from the original strand of the carriageway, crosses to the more-recently constructed strand, and then continues to join another footpath, will be excepted.

D.4. This example on the Worthing Road near Southwater, West Sussex would be excepted, along with the continuation west to Hartsgravel Bridge. The easterly strand of the road is the original turnpike line, the westerly strand later constructed for northbound traffic.

D.5. If there were a continuation east to the nearby Bar Lane, this too would be excepted. And indeed, older maps do show such a continuation, which is unrecorded. It is not clear whether such a continuation will in this case be excepted because the footpath between the two strands of the same carriageway is already recorded on the definitive map and statement. In my view, the more likely answer is not, because s.53 does not apply to the footpath which lies between the two strands of the Worthing Road carriageway (see s.53(1)(b)), and therefore there is nothing to trigger the exception. But the alternative cannot be ruled out, because if the intention is to preserve the entirety of the way, then it might be seen as immaterial that any part of it is already recorded, if another part remains vulnerable to extinguishment.

D.6. There is an argument that the continuation of the same footpath or bridleway either side of the two strands of the same carriageway is not excepted. That is because subs.(3)(a) excepts only a footpath or bridleway which extends from the excepted part (i.e. between the two strands of the same carriageway) ‘to, but not beyond, a retained highway’. The argument might be that either the path does not extend from the excepted part at all, because the continuation is on the other side of the carriageway, or that because the excepted part itself connects with a retained highway (i.e. each of the two strands of the carriageway), nothing beyond it can be excepted. However, because subs.(3)(a) has express application to such a case (see subs.(3)(a)(ii)), it seems proper to construe the provision as intending to have some excepting effect in appropriate cases, rather than being entirely sterile.

See subs.(1)(c)(ii), (3)(a)(ii), (3)(b) and (4).

E. Modern diverted paths

E.1. It is a footpath or bridleway which was diverted, widened or extended by order or other instrument after 1 January 1949.

E.2. The modern suite of powers to divert and extinguish footpaths and bridleways first was conferred in ss.42 and 43 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 (these came into force at the end of 1949): they now are re-enacted in ss.118 and 119 of the 1980 Act.

E.3. However, there are a range of other provisions, some of which predate 1949, by which footpaths or bridleways can be diverted by order. One of these is s.116 of the 1980 Act, which enables a highway to be diverted by order of the magistrates’ court.

E.4. The 1949 Act also conferred new powers in ss.39 and 40 for local authorities to create footpaths and bridleways by agreement or compulsorily by order: they now are re-enacted in ss.25 and 26 of the 1980 Act. And parish councils have long had powers to create new highways by agreement (originally in s.8(1)(g) of the Local Government Act 1894, now contained in s.30 of the 1980 Act). Of course, paths created using powers conferred after 1949 will not be at risk of extinguishment.

E.5. If a footpath or bridleway has been diverted, widened or extended by any of these mechanisms since 1 January 1949, then it will be excepted from extinguishment.

E.6. It will be unusual that a footpath or bridleway has been affected by one of these mechanisms and not recorded on the definitive map and statement.

E.7. It is not only the footpath or bridleway which has been diverted, widened or extended which is excepted, but a continuation of the same footpath or bridleway to connect with another highway (which is not itself extinguished). For example, a bridleway between village A and village B, connecting intermediately with no other highway, was diverted by order in 1950 so that a small part of it went round the edge of a field instead of straight across. The bridleway was not added to the definitive map and statement. The whole of that way is excepted from extinguishment.

E.8. However, in our example, if that bridleway, between the diverted part and village A, intersected with a footpath which was recorded on the definitive map and statement, then the part from village A as far as the intersection would not be excepted and would be extinguished—even though that would isolate the excepted part for horse riders and cyclists.

See subs.(2)(a), (3)(a)(ii), (3)(b) and (4).

F. Stopped up bridle rights

F.1. It is a footpath over which bridle rights were extinguished by order after 1 January 1949.

F.2. This will have happened very seldom (and still more seldom that the footpath then failed to be recorded on the definitive map and statement).

F.3. It is not obvious which mechanisms could be used to stop up only bridle rights over a bridleway, so as to leave a footpath. It could be done by Act of Parliament (and there may be some bridle crossings of railways where this was done). It probably could be done by a magistrates’ court under s.116 of the 1980 Act. It might perhaps be done under s.247 or s.257 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. Combined orders to stop up a bridleway under s.118 of the 1980 Act and create a footpath under s.26 would appear not to satisfy the requirement of this provision in subs.(2)(b), because the path was not one which ‘became a footpath…by the stopping up of a bridleway’ but by the creation of a footpath—but the footpath would in any case be post-1949 in origin and not subject to extinguishment.

F.4. It is not only the footpath over which bridle rights have been stopped up which is excepted, but a continuation of the same footpath or bridleway to connect with another highway (which is not itself extinguished). Thus, if bridle rights were stopped up over part of the length of a bridleway by an order of the magistrates court in 1964, reserving a footpath over the former bridleway, then the entirety of the bridleway is excepted from extinguishment as far, in each direction from the stopped-up part, as the first junction with a highway which is not extinguished.

F.5. Where a road was stopped up from 1949 or later with reservation of a footpath or bridleway, no exception is given or needed, because the footpath or bridleway was not a footpath or bridleway pre-1949 (see s.53(1)(a)).

See subs.(2)(b), (3)(a)(i), (3)(b) and (4).

G. Bridle rights acquired over footpaths

G.1. It is a footpath over which bridle rights have been acquired since 1 January 1949.

G.2. The Defra Secretary of State has, as noted in para.A.9. above , said that she (as the Secretary of State then was) does not intend to comply with the recommendation of the Stakeholder Working Group, that pre-1949 unrecorded rights of way in continuing use should be excepted from extinguishment.

G.3. But this provision will have very similar effect in certain circumstances. Where a pre-1949 footpath has been used by horse riders, as of right, for a period of at least 20 years since 1949, sufficient to establish bridle rights over the footpath, then the footpath, now having the status of a bridleway, is not extinguished.

G.4. It is not only the pre-1949 footpath, now bridleway, which is excepted, but a continuation of the same footpath to connect with another highway (which is not itself extinguished). For example, a pre-1949 footpath between village A and village B leading across common B, is unrecorded. Horse riders have used part of the footpath, where it crosses common B, for more than 20 years as of right, and that part now has the status of a bridleway. The whole of that way (part now bridleway, part footpath) is excepted from extinguishment.

G.5. The position may be different if the use of the common by horse riders has established other bridleways on the common connecting with the footpath (now bridleway). In that case, it may be that only the part of the footpath which is now a bridleway is excepted, and the remaining part is extinguished. That is because subs.(3)(a) excepts only a bridleway which extends from the excepted part (i.e. the footpath now bridleway) ‘to, but not beyond, a retained highway’. The argument might be that because the excepted part itself connects with a retained highway, i.e. the other bridleways established on the common, nothing beyond it can be excepted.

G.6. Nevertheless, this exception may have quite powerful effect where pre-1949 footpaths are unrecorded, but have been in continuing use both on foot and on horseback. But note that this exception applies only to bridle rights acquired from 1949, over a pre-1949 footpath which is not shown in the definitive map and statement.

G.7. Where bridle rights have been acquired from 1949 over a pre-1949 footpath which is shown in the definitive map and statement, those higher rights will not be extinguished, because there is no provision to that effect contained in s.53.

G.8. In effect, therefore, bridle rights acquired from 1949 over a pre-1949 footpath are not extinguished, regardless of whether the way is or is not included in the definitive map and statement as a footpath.

G.9. It is all the odder, therefore, that where there are unrecorded bridle rights, established before 1 January 1949, over a way recorded in the definitive map and statement as a footpath, those rights will be extinguished by s.53(4)(a).

G.10. Note the double evidential burden here: one will need to prove not only that the way is a pre-1949 footpath, but that user evidence shows that bridle rights have been acquired over it. In practice however, if one proves the user evidence as a bridleway, it may not matter much, or at all, to show that there was a historical footpath. (The landowner might wish to try to show that there was a pre-1949 bridleway which had been extinguished.)

G.11. The exception also will apply where bridle rights have been created over a pre-1949 footpath, whether by express dedication or by means of a creation order. Neither scenario is very likely. Suppose, for example, that there is an agreement to create a bridleway along a green lane, leading to express dedication at common law. The way is not put on the definitive map and statement (perhaps because the surveying authority is leery about treating express dedication as a legal event which would allow it to make a legal-event modification order). It turns out subsequently that the green lane is an unrecorded pre-1949 footpath. This exception ensures that, although the way is not recorded, whether as footpath or bridleway, and is pre-1949 in origin, it is not extinguished. (Note that the pre-1949 footpath does not become a post-1949 bridleway, not subject to extinguishment under s.53, owing to the dedication. That is because in general s.53 applies to pre-1949 footpaths and bridleways which are, at the cut-off date, unrecorded footpaths or bridleways. The instrument of dedication has upgraded the footpath to bridleway, but it would still fall within the scope of s.53 extinguishment were it not for the statutory exception.)

See subs.(2)(c), (3)(a)(i), (3)(b) and (4).

H. Reduced-width footpath or bridleway

H.1. It is a footpath or bridleway, of which part of the width has been stopped up after 1 January 1949.

H.2. It is unusual for part of the width of a footpath or bridleway to be stopped up (and still more unusual that the footpath or bridleway then failed to be recorded on the definitive map and statement).

H.3. A partial-width stopping up probably could be done by a magistrates’ court under s.116 of the 1980 Act, or under s.247 or 257 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. It could also be done by a partial width extinguishment order under s.118 of the 1980 Act. It seems that, where part of the width of a footpath is converted to a cycle track under the Cycle Tracks Act 1984, so that part of the width remains unaffected, the exception would not apply, because the converted part of the footpath has not been ‘stopped up’. In that (unlikely) scenario, only the unconverted part of the unrecorded footpath would be extinguished.

H.4. It is not only the footpath or bridleway over which part of the width has been extinguished which is excepted, but a continuation of the same footpath or bridleway to connect with another highway (which is not itself extinguished). For example, a bridleway lies between village A and village B, connecting with no other intermediate highway. Part of the bridleway was set out in an inclosure award at 20 feet wide. A housing estate was built abutting the bridleway in 1968, and the width of the bridleway next the housing estate was reduced to 12 feet by order under s.257 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. The bridleway was not added to the definitive map and statement. The whole of that way is excepted from extinguishment.

H.5. But if, in building the housing estate, the bridleway (beyond the reduced-width section) was made to connect with adopted estate roads, then only the reduced-width part, and so much more either side as connects with the adopted roads, will be excepted from extinguishment.

See subs.(2)(d), (3)(a)(i), (3)(b) and (4).

I. Bridges and tunnels

I.1. It is a footpath or bridleway ‘as passes over a bridge or through a tunnel’.

I.2. It is not only the footpath or bridleway which passes over a bridge or through a tunnel which is excepted, but a continuation of the same footpath or bridleway to connect with another highway (which is not itself extinguished). For example, a footpath lies between village A and village B, connecting with no other intermediate highway. Part of the footpath crosses a bridge. The footpath was not added to the definitive map and statement. The whole of that footpath is excepted from extinguishment.

I.3. Neither ‘bridge’ nor ‘tunnel’ is defined by the 2000 Act.

I.4. It appears to be immaterial by whom the bridge is provided. For example, it does not matter that the bridge is owned and maintained by the landowner for his or her own convenience, so long as the footpath or bridleway way passes over it.

I.5. It seems that a bridge need not be of any great substance in order to qualify as a bridge. For example, a plank over a ditch appears to be sufficient. A culvert underneath a path appears unlikely to qualify.

I.6. S.34 of the 2000 Act refers to powers to create a ‘means of access’ to access land, including ‘any bridge, stepping stone or other works for crossing a watercourse, ditch or bog’. If ‘bridge’ is used in the same sense in both s.34 and s.54, it includes quite minor works.

Photo © Ian Capper (cc-by-sa/2.0)

I.7. On the face of it, a tunnel suggests a subterranean passage of some length. (OED: ‘A subterranean passage; a road-way excavated under ground, esp. under a hill or mountain, or beneath the bed of a river: now most commonly on a railway; also in earliest use on a canal, in a mine, etc.’) However, such features are almost wholly absent from the recorded rights of way network, let alone unrecorded rights of way, and it would be surprising if unnecessary provision were made to except from extinguishment. It also would be surprising if a footpath or bridleway over a bridge (such as a railway bridge) were excepted, but not a path under a bridge (again, such as a railway bridge). It is unclear how one would distinguish a long under-bridge from a short tunnel: for example, some of the Lovelace Bridges (East Horsley, Surrey) have the appearance, for users, of tunnels (see, for example, Meadow Plat bridge), but were built as over-bridges for forestry purposes. A cattle creep under a railway line likewise has the appearance of a tunnel (see, for example, the creep at Charlton, Hampshire, which conveys a footpath under the railway).

I.8. It is unclear whether the bridge or tunnel must still be in existence at the cut-off date. In the example in para.I.2 above , if it is well documented that the footpath crosses a bridge (being marked on successive editions of the Ordnance Survey County Series plans), but the bridge no longer exists, does the exception apply?

I.9. It is possible that the exception is intended to preserve from extinguishment unrecorded rights of way which benefit from infrastructure provided at public expense, or where such infrastructure was provided at private expense (such as by a railway or canal company) in order to satisfy the public interest in maintaining the right of way. If so, it would be reasonable to interpret a ‘tunnel’ to include an under-bridge, and for such infrastructure still to be in place at the cut-off date—otherwise the effect would be to require, in effect, the replacement of the missing infrastructure at considerable new expense. The use of the present tense in subs.(2)(e) reinforces that conclusion. However, if so, the position is unclear where the decking or cover has been removed from above an under-bridge, so that the infrastructure remains present and passable, but no longer functional (i.e. the roof of the ‘tunnel’ has been removed).

I.10. It appears not to matter whether the pre-1949 footpath or bridleway passed over the bridge, or through the tunnel, prior to 1949. If, for example, the footpath or bridleway passes over a motorway on a bridge constructed (inevitably) after 1949, but on a line which is consistent with the pre-1949 way, this seems to be sufficient to attract the operation of the exception.

I.11. The scope of the exception is uncertain in its impact, so that what might be excepted ranges from a footpath crossing a stream where the footbridge long has been washed away, to a former tunnel under a four-track railway line and sidings, where the line has closed and the decking removed.

See subs.(2)(e), (3)(a)(i), (3)(b) and (4).

J. Created right of way over pre-1949 footpath or bridleway

J.1. It is a pre-1949 right of way over a post-1949-created right of way.

J.2. This is best illustrated by an example. A bridleway lies between village A and village B, connecting with no other intermediate highway. It is pre-1949 in origin, and was unrecorded on the definitive map and statement drawn up under the 1949 Act. In 1972, unaware of the pre-1949 bridleway, the local authority created a footpath along part of the line of the bridleway by agreement under s.25 of the 1980 Act to facilitate access within a new housing estate. The bridle rights over that part of the created ‘footpath’ are excepted from extinguishment.

J.3. No other part of the bridleway benefits (in this class) from the exception from extinguishment.

J.4. Plainly, the exception is of relevance only where the rights which subsequently have been created are of lower status than the pre-1949 rights. If, for example, a public road is created over the line of the bridleway in the example in the previous paragraph, the exception is of no real effect.

J.5. There is an express exclusion from the operation of this exception in respect of the rights conferred for cycling under s.30 of the Countryside Act 1968.

See subs.(5)(a).

25 January 2024: paragraph G.11. added following a recent comment.