Introduction

If one was to compile a list of post-war initiatives to promote public access to the countryside, what might appear? Certainly, any list should include:

- the definitive map of public rights of way (under Part IV of the National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act 1949);

- the depiction of definitive public rights of way on Ordnance Survey maps (from 1960, apparently on the initiative of the Ramblers’ Association)

- the right of access to open country and registered common land (conferred by Part I of the Countryside & Rights of Way Act 2000)

- the power for local authorities to provide country parks, the signposting of public paths, and the right to ride cycles on public bridleways (under the Countryside Act 1968)

Perhaps too, recognition should be given to the efforts of access organisations, and particularly the Ramblers’, to secure better recognition by local authorities of their responsibilities to maintain and promote their public rights of way networks.

But there is one more candidate for inclusion: ORPA. No, not the killer whale, but ‘Other Routes with Public Access’, a symbol used by the Ordnance Survey (OS) on its leisure mapping since about the turn of the present century to represent selected public highways which are not public rights of way on the definitive map and statement. The idea for ORPA seems, again, to have originated with the Ramblers’ Association. (Ironically, ORPA is also an initialism of the Off Road Promoters Association, which has a particular interest in these routes.)

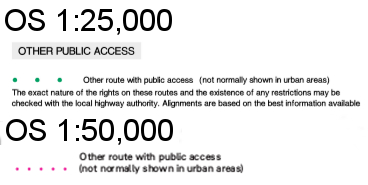

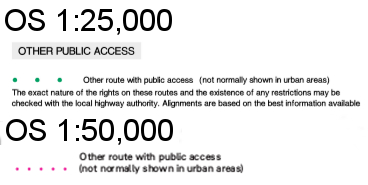

ORPA symbols

Here are the ORPA symbols used on the OS’ 1:50,000 and 1:25:000 maps:

What are ORPA? The OS uses the following text in its key: “The exact nature of the rights on these routes and the restrictions may be checked with the local highway authority”. Which is mystifying and unhelpful but consistent with the OS’ practice of minimising its responsibility for the existence of a right of way along any route shown on its maps.

The list of streets

The provenance of ORPA is the list of publicly maintainable streets held by every local highway authority under s.36(6) of the Highways Act 1980: this sparsely worded provision simply requires that, “The council of every county, metropolitan district and London borough and the Common Council shall cause to be made, and shall keep corrected up to date, a list of the streets within their area which are highways maintainable at the public expense.” Subs.(7) goes on to provide that the authority must keep the list available for public inspection at its own office, and the relevant part at the office of any district council (if there is one). And ‘street’ is given the meaning assigned to it in s.48(1) of the New Roads and Street Works Act 1991, which is to say: “any highway, road, lane, footway, alley or passage, any square or court, and any land laid out as a way whether it is for the time being formed as a way or not.” Although this definition has a rather Dickensian feel to it in its reference to ‘passage’, ‘square’ or ‘court’ (similar language can be found in the definition of a ‘street’ in s.3 of the Town Police Clauses Act 1847), there seems to be little doubt that the list of streets must identify any public way, whether in the countryside or in town, which the highway authority is obliged to maintain. And this includes not only the main roads in the authority’s area (but not trunk roads nor motorways: these are maintained by Highways England), but also most residential roads, country lanes, byways open to all traffic, restricted byways, public bridleways and footpaths, just so long as they are publicly maintainable. Whether any particular way is in fact publicly maintainable will be a matter of provenance and history: for example, any public road in existence before the Highway Act 1835 is publicly maintainable, and most public rights of way are — but there are exceptions, including footpaths added to the definitive map of rights of way since 1949 on the basis of long use.

It follows that the list of streets should have a vital role in the highway authority’s functions: it tells the authority, and the public, which highways the authority must maintain, and by implication, those ways (some of which will nevertheless be public highways) which it does not maintain. In practice, the role of the list of streets has been eclipsed for two reasons: first, because highway authorities focus on maintaining the ‘street works register’ required under s.53 of the New Roads and Street Works Act 1991, which must show every street for which the highway authority is the ‘street authority’ (r.4(5) of the Street Works (Registers, Notices, Directions and Designations) (England) Regulations 2007), and the highway authority is the street authority for every publicly maintainable highway, s.49(1)(a). And secondly, because few highway authorities include all publicly maintainable rights of way in their list, even though it seems they should.

How ORPA were identified

Nevertheless, it is the list of streets which provides the provenance of ORPA. The OS has explained to me (in a letter of 2008) that “ORPA were collected [from highway authorities] as a one off exercise approximately ten years ago. Field surveyors visited the local authority highways department and selected from the local authority list of streets with the objective of linking gaps in the existing rights of way network. The list is not comprehensive, for example ORPAs are not shown in urban areas. Currently there is no mechanism in place to update them.” The implication is that it was the OS which selected, from routes shown in the list of streets, those ways which were appropriate to be depicted as ORPA. Remember that most entries in the list relate to the conventional tarred roads in the authority’s area: so the OS was not interested in showing as ORPA roads which were already coloured on its 1:25,000 and 1:50,000 maps, nor in marking ORPA along residential roads which might be assumed to be part of the ordinary highway network. What the OS was targeting was those highways, mainly in rural areas, which were included in the list of streets, but which if they appeared on the OS map at all, did so as ‘white roads’, and where the map user might at best be uncertain about whether there were any public right of way, and at worst, might well assume that there were none, or have no reason to suppose that any existed at all. Uncertainty about public rights was compounded by the untarred character of many of these highways, so that they might be green lanes, or cross field tracks, but with little or no evidence of their legal status. In practice, the public status of some of these ways was transparent: perhaps they were included as part of a National Trail, or they were the only means of access to the start of one or more public paths (although it is not inevitable that a public path begins on another public way). Alternatively, tell-tales of public status might have been discernable to the experienced user: perhaps traces of a tarred surface put down in the 1920s and not maintained since the Second World War, or a highway authority ‘Unsuitable for Motor Vehicles’ sign, which, in the perverse language of bureaucracy, can be roughly translated as ‘Public road which we must maintain for motor vehicles, but don’t’:

Unsuitable for motors: The Drift, off Denton Lane, Harston, Leics © Alan Murray-Rust and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

The consensus seems to be that it was the OS which decided what to depict as ORPA, and what to exclude, given access to the entire list of streets. It may be that in some highway authority’s areas, a more prescriptive approach was taken, where the highway authority provided ‘advice’ on what it wanted to be shown, and what it wanted excluded. In many areas, it remains unclear why some ‘white roads’ have been marked as ORPA, and others (known to be included in the list of streets) have not. For example, in Surrey, which has relatively few unsealed public roads, many were either overlooked or excluded from the original survey, but have now been recognised for inclusion in the next edition of the relevant OS maps. In deciding what to show, the OS appears to have adopted some basic rules:

- ‘coloured’ roads are never shown as ORPA (colouring in practice means the road is either a public road, or in the odd few exceptions, open to the public, though possibly tolled: see the OS statement here)

- selectivity is exercised even over what is otherwise eligible (e.g. whether to depict ORPA along an isolated residential road)

- ORPA is not shown where the route is on the definitive map and is therefore shown as a public right of way (even if ORPA implies there may be higher rights)

This last point means that some ORPA are shown as discontinuous, alternating with say a public footpath where the definitive map public right of way lies alternately inside and outside the boundaries of the green lane.

What rights are implied by ORPA?

This bring us to the question of what exactly can be inferred from a route being marked as ORPA? The inclusion of a way in the list of streets technically confirms only that the highway authority accepts that it has a duty to maintain the way (and even then, mistakes are sometimes made, so that ways are wrongly included in the list, and significant numbers of ancient ways may be omitted from the list — not to mention all those rights of way wrongly excluded in most local authority areas). Inclusion does not of itself confirm the status of a way, although it is a safe assumption that if a way is publicly maintainable, it must be at least a public footpath. In practice, most county highway authority’s lists of streets comprise three classes of publicly maintainable ways:

- main roads which have long been the maintenance responsibility of the county council

- local roads, responsibility for maintenance of which was formally transferred to county councils under s.30 of the Local Government Act 1929 (as noted in my blog on Bradley Lane or Bradley Path?)

- urban paths and alleyways, which are typically tarred, and have traditionally been maintained as part of the urban street network

This is a broad simplification: practice varied across county councils, and in urban boroughs, what is contained in the list may be a complete inventory of known public rights of way. Indeed, some boroughs were wholly excluded from the requirement to draw up definitive maps of public rights of way until s.55(3) of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 was brought into force, and even now, lack comprehensive definitive maps for their areas. Bradford is the most egregious example, but in compensation, its list of streets contains details of most of the public rights of way within the former city borough, and the OS has brought that information to life by showing the extensive network as ORPA (see for example this photo of a bridge over a beck near Thornton, Bradford, which is marked on the OS map as ORPA, but which is apparently no more than a footpath). In a typical rural county area, there is a pretty strong likelihood that any way depicted as ORPA and therefore shown in the list of streets is an old vehicular highway — but likelihood is not proof, and from time to time, definitive map modification orders are made for such ways which achieve no more than bridleway status (Bradley Lane is one such example).

Updating ORPA

The OS considers the collection of list of streets data to have been a one-off exercise, and has no plans to review or update the data. In the author’s experience, the OS will make changes only on instructions from the highway authority, and is reluctant to act on any third party intervention, although user groups have secured increased coverage in some areas (such as Norfolk). I infer the OS position currently to be that:

- new routes must be validated by the highway authority (the OS says it no longer holds the original survey data, so it is unable to validate nominations against those data), including confirmation that the authority considers the route suitable for depiction, so that the OS has assigned editorial discretion to the authority

- the OS will consider adding only routes which are in the list of streets

This means that, where the highway authority is not pro-actively taking an interest in the ORPA data, and engaging with the OS (and given that in most authorities, unsurfaced roads are still managed by the highways team rather than the rights of way team, there’s precious little resource or zeal for these routes), the ORPA data are sterilised, with perhaps the odd route dropping off the map when somebody complains to the authority, and the authority takes the line of least resistance by calling for it to be quietly removed from the OS map (such action of course technically having no impact on public rights).

The OS will not consider adding privately maintainable public highways as ORPA, nor public highways not maintained by anyone, even though these fit the description of ‘other routes with public access’. In a 2010 report to a committee of Devon County Council concerning a network of lanes south of Honiton which had been subject to a ‘cessor’ order (i.e. the court had ordered that the lanes should cease to be publicly maintainable), it states that the matter was concluded with the “Town Council resolving to ask the County Council to request the Ordnance Survey to depict this section as available for public use. Ordnance Survey was contacted accordingly, and the route appears marked accordingly on its most recent mapping” (see streetmap). However, whatever the past policy, it appears that the OS will not now do this — though why not is unclear.

The future for ORPA and the CROW Act 2000

Many unsurfaced roads in the countryside have been affected by Part 6 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 (NERC2006), which extinguishes rights for mechanically propelled vehicles over certain public carriageways. Generally speaking, NERC2006 will not have extinguished rights over list of streets routes, because s.67(2)(b) specifically exempts from extinguishment ways which were included in the list at the date of commencement. (Ways which were both included in the list and shown on the definitive map are not automatically exempted, but these will not be shown on the OS map as ORPA.)

There is also the question of whether these ORPA are threatened by the extinguishment of rights of way in 2026 (or later if delayed by regulations) under Part II of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (CROW2000). The short answer is generally no: first, because carriageways are not affected by Part II, and secondly because there is an expectation, endorsed by the stakeholder working group on rights of way, that routes on the list of streets (and therefore underpinning almost all ORPA) in 2026 will be preserved from extinguishment even if they are not carriageways, on the grounds that they are duly recorded, even if not on the definitive map and statement.

The longer, more careful answer, is probably not in most cases. Some hesitancy is called for because in some circumstances, ways now shown as ORPA will (on currently understood criteria) be eligible for extinguishment because:

- a way shown as ORPA on the OS map is erased from the list of streets by 2026 (whether by due process or otherwise), and also is not a carriageway

- a way shown as ORPA on the OS map was not sourced from the list of streets, and is privately maintainable, or not maintainable at all (see the Devon example above), and also is not a carriageway

- there may be no comprehensive exemption of list of streets routes in regulations and the way shown as ORPA on the OS map is also not a carriageway

- amending legislation is passed to extend the CROW2000 provision to unrecorded carriageways, and any of the above applies irrespective of whether the way is a carriageway

Some of these outcomes could occur de facto on the basis of a particular way shown as ORPA on the OS map being assumed to be a public footpath or bridleway, and not a carriageway, and it being asserted that public rights have been extinguished. Since there is no automatic administrative or judicial process to confirm whether a right of way has been extinguished under Part II of CROW2000, this may be a significant practical difficulty. Indeed, under s.54A of the Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981 (inserted by para.4 of Sch.5 to CROW2000), no carriageway may be added after 2026 to the definitive map and statement (or any later date substituted by regulations) as a byway open to all traffic, so even if a way is considered to be a carriageway, there will be no accessible mechanism available to users to demonstrate that the way is a carriageway, still less any means to preserve a public record of that status for perpetuity in a definitive map and statement.

Conclusion The inclusion of ORPA on OS leisure mapping has promoted substantially improved access to the countryside in areas where untarred roads are a significant part of access opportunities — and it has demonstrated how widespread such access can be, and how poorly was publicised information about this access previously. It must be said that the OS’ diffidence about the rights available over ORPA leaves some map users bemused about precisely what rights exist — but then that largely reflects the uncertainty inherent in the data. Just by way of illustration, consider how widespread are the ORPA in this area of Stokeinteignhead in South Devon. Pre-ORPA, any visitor to the area would have struggled to determine whether this extensive network of charming but unsignposted untarred lanes were public or private. Now, the OS map confirms that these delightful lanes, such as this one, can be enjoyed by all:

Unsealed public road to Lower Rocombe near Stokeinteignhead, Devon (photo by the author)