Part II of the 2000 Act widely is understood to extinguish, by default in 2026, public paths which are not recorded on the definitive map and statement — subject to as yet unspecified savings for, for example, paths the subject of pending applications for definitive map modification orders. What is less widely understood is that, in 2015, Defra adopted the position that Part II also extinguishes any unrecorded widths of public paths — that is, any width which exceeds that recorded in the definitive statement (if any width is recorded at all). Defra has proposed that the extinguishing effect on width should be subject to a saving for such width ‘as is necessary for the safe and convenient passage of the public’. This blog analyses what impact the extinguishment of unrecorded width might have.

A. Introduction

A.1. Section 53 of the Countryside and Rights of Way (CROW) Act 2000 extinguishes certain unrecorded footpaths and bridleways of historical origin.

A.2. The Stakeholder Working Group (SWG) has been informed that s.53 bites to extinguish the unrecorded width of footpaths and bridleways of historical origin (i.e. pre-1949) which are nevertheless recorded on the definitive map and statement.

A.3. This is an analysis of the effect of s.53 in relation to unrecorded width.

A.4. Reference is made below to a ‘true width’ of a right of way, meaning the width which may be established either by dedication (express or deemed), or by statutory origin (such as an inclosure award or diversion order where a width expressly is given).

A.5. Reference is made below to ‘public paths’, meaning footpaths and bridleways (only).

A.6. ‘EEW’ refers to the extinguishing effect on width — see para.C.1 below; ‘SCW’ refers to the ‘safe and convenient’ width — see para.E.19 below.

B. The origin of widths in the definitive statement

B.1. Part IV of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 (the ‘1949 Act’) called for the preparation of the draft, provisional and definitive map and statement of public rights of way by surveying authorities, relying (s.28) on the provision of information by, inter alia, parish councils and parish meetings.

B.2. S.27(4) required the surveying authority to prepare:

…a statement…containing…such particulars appearing to the authority to be reasonably alleged as to the position and width [of public rights of way shown in the map], or as to any limitations or conditions affecting the public right of way thereover, as in the opinion of the authority it is expedient to record in the statement.

B.3. S.31(1)(c), (3)(c) and (5) provided for appeals to quarter sessions against the width entered in the provisional statement. S.32(4)(c) provided that:

…any particulars contained in the [definitive] statement as to the position or width [of a right of way] shall be conclusive evidence as to the position or width thereof at the relevant date…

B.4. The width of a way specified in the definitive statement is most likely to have derived from the parish survey conducted under s.28. What was recorded in the parish survey may follow from a conscientious assessment of the true width of the way, a guess or general statement of its width, or a standard formula (such as that every footpath has a width of 2 feet). Even where the width recorded in the definitive statement arises from first-hand assessment during the Part IV survey, it should not be assumed that the recorded width is reliable. It is unlikely that, on a survey of parish paths, the surveyors (in practice, parish councillors, volunteers or user group representatives) made detailed measurements of the paths. On a cross-field path, a width might be recorded which reflected the extent of any worn path on the ground; on an enclosed way, a width might be estimated as the average width between the boundary fences, walls, hedges or ditches. Even if measurements were taken, it is unlikely that they were repeated at regular intervals. The width recorded is highly unlikely to be, nor intended to be, an accurate measurement of the entire width of the way throughout its length. Indeed, it might be qualified in terms: ‘average width of 16 feet’; ‘worn path 2 feet wide’; or ‘2 foot path within lane 12 feet wide’.

B.5. Where no width was recorded in this parish survey, it is possible that a width was inserted by the surveying authority. As it is unlikely that the authority had the resources to measure every way, such a width was more likely to adopt a standard formula than an attempt accurately to record the width of the particular way.

B.6. It should be noted that, even assuming that a surveyor was equipped to take measurements, and that those measurements faithfully were recorded in the definitive statement, the surveyor incorrectly may have relied on physical features in order to make an informed assessment of the true width. In relation to a cross-field footpath, the worn width of the way might be no more than was rolled out by the farmer in that particular year; in relation to an enclosed lane, the true width might lie between the roots of the hedges and not between the inner sides of the ditches within the lane.

B.7. In relation to rights of way in the West Riding of Yorkshire, a decision was taken1 that any footpath recorded (in the draft statement) with a width of more than 6 feet summarily was to be reduced to 4 feet, and bridleways likewise more than 10 feet wide to 8 feet,

‘to define the liability of the highway authority within the limits of ways which in some cases are 20, 30 and sometimes more feet between fences.’

Subsequently, it appears that the reduced width was imposed only where an objection was made by the district council — but many such objections were made, instigated by the highway authority. Thus the decision acknowledged that the true width of those ways was often much wider. These ways now are recorded in the definitive statement with a width of 4 feet (for footpaths) and 8 feet (for bridleways). It is calculated that at least 2,140 modifications of width or status or both were made by, in effect agreement between district and county council, in the West Riding area.2

B.8. It has been suggested that other surveying authorities adopted a standard width of, for example, 2 feet in relation to every public footpath in their area — even where the footpath followed a green lane or road.

B.9. The recorded width, if any, therefore is not necessarily a reliable or useful guide to the true or historical width of the way. It may bear no relation whatsoever to either measurement.

C. Extinguishing effect on width

C.1. Section 53 is said to have possible effect in extinguishing all or part of the width of a right of way in two circumstances:

- where a way is recorded in the definitive map and statement but with a width defined in the statement being less than the true width;

- where a way is recorded in the definitive map and statement but with no width specified (a ‘null width’).

This is referred to below as the extinguishing effect on width — the EEW.

C.2. This analysis does not review the correctness of the EEW as such, but proceeds on the assumption that it is correct in relation to the first case, and argues that it is untenable in relation to the second case.

C.3. In relation to the second effect, the EEW (if there is an EEW) must have effect to extinguish the way in its entirety. In the absence of any saving provision to moderate the effect of the EEW, there can be no half-way house — either the entire way is extinguished for want of a defined width in the definitive statement, or it is unaffected

C.4. It is understood that the recording of rights of way with a null width is so widespread that an interpretation which infers the extinguishment of all such ways (if they are of historical origin) in the absence of a saving provision appears inherently absurd and contrary to the intention of Parliament. There is a presumption against Parliament legislating for an absurdity, and:

the strength of these presumptions depends on the degree to which a particular construction produces an unreasonable result. The more unreasonable a result, the less likely it is that Parliament intended it3

C.5. Such an interpretation cannot be rendered acceptable if that rendering is achievable only by the enactment of a saving provision in secondary legislation which heads off the outcome effected by s.53 itself. Delegated legislation may be used as an aid to interpretation primarily where it is contemporaneous with the Act.4 Were it clear during the Parliamentary stages of the CROW Bill that it was intended to make regulations to moderate the effect of s.53 in relation to unrecorded widths, it might be possible to make a case that, taken together — the Act and the proposed regulations — were intended to extinguish rights of way with a null width subject to a specified saving of partial width. But not only was no such intention evinced at the time, and draft regulations to give effect to such a saving not published until nearly 20 years later, but (as noted above, and see section D below), there was no perception of any EEW at the time of the CROW Bill, or in the years following its enactment. Moreover, full effect can be given to s.53 for the purpose to which it is plainly addressed (‘Extinguishment of unrecorded rights of way’5) without interpreting it to have full extinguishing effect in relation to ways which are recorded with null width.

C.6. Thus it is submitted that s.53 must be interpreted without recourse to the moderating effect of any implementing regulations, and that, if there is an EEW, only the first effect is tenable. Therefore, only the first effect here is considered further.

D. Acting on the extinguishing effect on width

D.1. Part II of the 2000 Act does not make any express provision to extinguish unrecorded width of any right of way.6 Nor do the explanatory notes address any such provision inherent in the legislation. No reference was made to any EEW during the debates in Parliament on the Countryside and Rights of Way Bill.

D.2. The report of the SWG7 does not address or refer to the EEW.

D.3. The author does not recall any articulation of an EEW prior to, during or in connecting with implementation of the 2000 Act.8

D.4. Accordingly, it appears that the earliest intimation of such EEW was its disclosure to the SWG (believed to be in 2015). On 22 December 2015, Jonathan Tweney of Defra circulated a note to the SWG,9 which summarised the view of Defra lawyers and counsel that there was no EEW in relation to the first case, but an EEW in relation to the second case (see para.C.1 above), and concluded:

The question is do we need an exception for under-recorded widths ie where the width recorded is less than the true width, such that they are saved from Section 53 extinguishment.

D.5. The questions which arise in this paper are broader: whether it is appropriate that the 2000 Act should have an EEW, and what might be done about it.

D.6. As to the first, approximately 15 years (or about three-fifths) of the 25 years allowed under the 2000 Act have passed without anyone (including those in Defra responsible for the legislation) having knowledge of the EEW (or if such knowledge did exist, raising awareness of it).

D.7. As to the second, it can safely be said that there is no awareness of the EEW outside the SWG, and no steps have been taken, by any party, to address it.

D.8. Moreover, even if such awareness were widespread, how would practitioners know what ways were threatened with partial extinguishment? And how would candidate public paths for research and safeguarding (through application for definitive map modification orders) fare with a little under five years until the cut-off date (one-fifth of the time originally allowed), set against the challenge of many other ways which would be extinguished altogether?

D.9. Few are familiar with the recorded width of public paths in the definitive statement. Even those who regularly work with the definitive map might rarely check with the details of width in the statement, save where a particular issue arises — for most, it is enough that the way is recorded on the map. Thus candidates for the EEW generally will be unknown.

D.10. In some surveying authority areas, candidates for the EEW may be commonplace, where (it is said), the authority habitually recorded a standard width on the draft definitive map under Part IV of the 1949 Act (e.g. 2 feet) regardless of the context. In others, they may be uncommon, where steps were taken to estimate the true width during the Part IV survey, and to research documents showing historical origin. Therefore, in order to identify candidates, a detailed survey would be required of all public paths compared with the definitive statement, and research carried out to identify those public paths which are attributable to an abstract specified width as opposed to survey.

D.11. Alternatively, a view could be taken that little or nothing should be done to prevent the EEW (perhaps by prioritising the safeguarding of unrecorded historical ways). If no saving provision were included in implementing legislation, then — where relevant — the EEW would substitute the width given in the definitive statement for the true width. In some contexts, this would substitute a width which bears no relation to need (e.g. 2 feet for a bridleway), or which leaves the way vulnerable to inclosure at an insufficient width (e.g. fencing a cross-field footpath to a width of no more than 2 feet).

D.12. Alternatively, if a saving provision is conferred, see the discussion which follows.

E. Analysis of the extinguishing effect on width

E.1. This section explores the issues which may arise from the EEW.

What is extinguished?

E.2. If part of the width of a public path is to be extinguished, the question arises as to which part will be extinguished? If, for example, a path is recorded with a width of 1 metre, but its true width is 3 metres, what is it which is extinguished in reducing the path with from 3 metres to 1 metre? Is the width reduced equally from both sides? So that 1 metre is eroded from one side and a further metre is eroded from the other side? Or is all the width lost from just one side? As there is no process prescribed in the legislation to apply the reduction in width to the specific circumstances of a particular public path, it must be assumed that the legislation works in the same way in relation to every path.

E.3. It may be that the definitive statement records the width of a public path in relation to defined features: for example, ‘3 feet out from the wall on the south side’. In that case, the EEW might be expected to have effect in relation to any part of the true width which lies beyond the recorded width (i.e. anything beyond 3 feet from the wall). But this will be exceptional.

E.4. If, say, a green lane bridleway is recorded in the definitive statement as ‘3 feet’ and the green lane is 12 feet wide, it could be said that the 3 feet is whatever 3 feet were in use at the time of the Part IV survey. If the path at the time of the survey then ran up the side of the green lane, then the retained 3 feet (following the EEW) would be the ‘original’ 3 feet at the side of the lane (and not a three foot strip up the middle). Of course, what part of the green lane was in use at the time of the Part IV survey may not be consistent with the part that is in use today, or indeed, pre-1949. Theoretically, this approach has some merit, in that it relates the definitive width to what was perceived at the time of the Part IV survey. But in practice, it is completely impossible to operate for want of knowledge of what was being used 70 years ago. If it were to be the correct approach, then plainly it is unworkable.

E.5. It is submitted that the only plausible and logical effect of a reduction in width, where the width in the definitive statement is not defined with precision in relation to any particular physical feature, is that the width equally is pared away from both sides of the path. While there may be circumstances (as to which, see immediately below) where it would make more sense if the width were lost entirely from one side of the path, it is impossible to conceive how the legislation could not have a universal impact applicable in every case.

E.6. This universal impact will have curious and undesirable effects. For example:

- If the path physically is enclosed on both sides, half the width will be extinguished between the fence (or other delimiting obstacle) and the new boundary of the path on each side, notwithstanding that the extinguished width on either side is unlikely to be of any use to any person other than the public using the path.

- If the path physically is enclosed on one side, half the width will be extinguished between the fence (or other delimiting obstacle) and the new boundary of the path on that side, again notwithstanding that the extinguished width is unlikely to be of any use to any person other than the public using the path. Whereas the owner of the land on the unenclosed side of the path will gain only the other half of the extinguished width.

- If the path comprises a metalled way eccentrically located within a broader strip of highway, or simply is maintained so that only a narrow trod is available to one side of the strip, it may be that part or all of the extinguished width will Include all or part of the metalled way or trod. Thus, what is left may comprise only the unimproved surface of the highway.

E.7. The photograph above shows Church Lane, recorded as a footpath. No width is recorded in the definitive map and statement, but let us assume that a width is recorded of 2 feet, and that the boundaries of the true extent of right of way are comprised in the wall and hedge on each side, amounting to a true width of 15 feet. If we are correct to infer that the EEW will occur on both sides of the right of way, what will be preserved is a 2 foot strip roughly centred on the right hand side of the paved footway. If a saving operates to preserve a greater extent, presumably what will be preserved is unlikely to be greater than the width of the paved footway (say 8 feet). Nevertheless inevitably some part of that paved footway will be extinguished, because half of what remains to be extinguished must be lost from the left hand side of the true extent of the right of way as a whole.

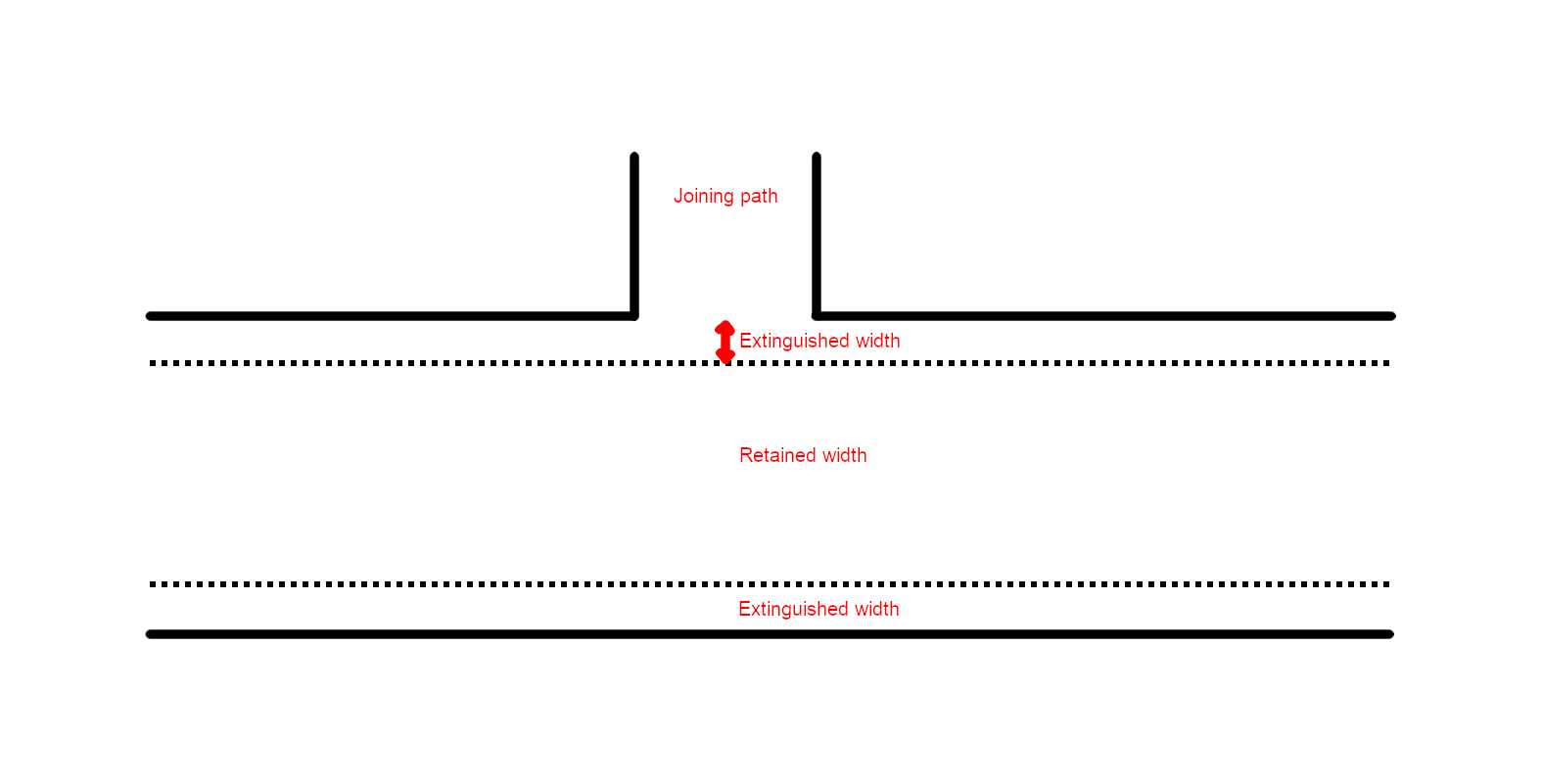

E.8. It is not clear what will be the outcome where a public path subject to the EEW is joined by another public path: see the example in Illustration 2 below. It seems that the EEW may cause part of the width of the path to be extinguished at the junction with the joining path (as elsewhere), creating a discontinuity between the two paths.

How much is extinguished?

E.9. What is extinguished must be that part of the way which is not recorded in the definitive statement as part of the specified width of the way (but see above about what part is extinguished).

E.10. Any saving contained in regulations may reduce or abrogate the EEW, to the extent that there may be no reduction in width whatsoever.

E.11. As we have seen (section B above), what (if anything) is recorded in the definitive statement as the width of a public path is by no means likely to be an accurate measurement of the true width of the path at the date of the Part IV survey. It may be a casual estimate of the path width, a guess as to width, an assessment of width of part of the path (only), or an administrative convenience. Nevertheless, the EEW removes such of the true width of the path which is not specified in the width entered in the definitive statement.

E.12. It is not clear what is the EEW where the width specified in the definitive statement is:

- uncertain (e.g. ‘average width of 5 feet’) or variable (‘between 5 feet and 8 feet wide’, or ‘narrowing from 8 feet to 5 feet’);

- not necessarily intended to specify the full width of the way (e.g. ‘tarred path 3 feet wide along green lane’);

- of uncertain extent (e.g. where a way is specified with an initial width of 12 feet along a farm drive, but later diverges from the farm drive without any acknowledgement of a change of width);

- ambiguous (it is commonplace in Surrey that the definitive statement includes both a ‘width’ and a ‘width fence to fence’).

E.13. Leaving aside any saving for unrecorded width (see below), the EEW may reduce the width of a public path to less than what is necessary to its use. This is a particular issue for horse riders: if the recorded, i.e. beaten width, of a bridleway is say 1 metre or 3 feet, then any further width will be subject to the EEW. If such a way is fenced to the recorded width, it will be impossible for two riders to pass. Moreover, if the path is of any length, and riders cannot, or do not, see that another rider is approaching from the other end, the situation will be quite serious — at best, one rider would have to dismount and coax the horse to back up over a possibly considerable distance, an action which is no more natural nor comfortable for a horse than for a human.

E.14. Many footpaths have been recorded with a width of say 2 feet. Such a width leaves insufficient room for two people to pass save with varying degrees of embarrassment, depending on the size of the individuals concerned.

E.15. If any public facility, such as a bench, post box or notice board, lies within the unrecorded width, the facility both would be isolated from public access, and (if installed reliant on powers in relation to highways) liable to be removed or relocated. Similar considerations might arise in relation to other features, such as a public well or access to water for livestock.

E.16. Where highway structures lie within the unrecorded width — such as ditches, drains, safety barriers, gates, stiles — these will cease to form part of the highway. The owner of the unrecorded width cannot be obliged to maintain (for example) a ditch which drains the highway, but forms no part of it.

E.17. It seems likely that many items of highway furniture, intended to control or facilitate passage by highway users — particularly gates and stiles — will be sequestered within the unrecorded width, or partly within it and partly within the remaining width of the highway. If so, the responsibility of relocating such furniture presumably lies with the landowner.

A saving for unrecorded width

E.18. It has been proposed that regulations might except from the EEW the unrecorded width of a public path in specified circumstances. At the time of writing, current drafting proposes that what should be excepted is:10

So much of the part of the [unrecorded] width…as is necessary for the safe and convenient passage of the public

E.19. Such provision of a ‘safe and convenient’ width (SCW), if made, could have a mitigating impact on the EEW. How would it operate?

E.20. The first point to note is that the SCW saving would operate only on the unrecorded width of the public path.

E.21. It is not stated in the draft regulation what SCW would be ‘necessary for the safe and convenient passage of the public’. A determination of the SCW must be applied as at the date of the cut-off (even if the determination itself is not made until later — as inevitably will be the case). Thus, for example, a cross-field footpath must, at the cut-off date, have some innate SCW, and if, ten years after the cut-off date, a definitive map modification order is made to determine the width of the footpath, that the footpath has now been fenced on both sides is irrelevant — the determination of the SCW is founded in a SCW as at the cut-off date.

E.22. As time elapses after the cut-off date, a determination of what was the SCW at the cut-off date will become increasingly difficult, where the context of the public path has been developed or otherwise modified — just as it is increasingly difficult to identify roads ‘whose main lawful use by the public during the period of [2001–06] was use for mechanically propelled vehicles’, for the purposes of establishing whether there was an extinguishing effect on public rights to use mechanically propelled vehicles.11

E.23. It is unclear whether the SCW might vary between public paths in different contexts. For example, it might be said that a footpath along a cliff-top ought to have a greater SCW than one along the edge of a grazed pasture. But that argument may rely on the special context of a cliff-top footpath, where the footpath lies close to the edge of the cliff-top, and the EEW would pare away at the offside width further away from the cliff-top, as well as the nearside next the clifftop.

E.24. But would a cross-field footpath, or bridleway, have a greater or lesser SCW than one enclosed between fences? It is not obvious that it should, in that the SCW ought to take account of the space necessary to ‘safe and convenient passage’ regardless of whether the public path is bounded by physical features. So for example, BHS guidance states that12:

A useable width [of 3m for a bridleway] is likely to require at least an additional half a metre to each side giving an overall width of 4 metres (bridleway)…to avoid such as overgrowth reducing the useable width between cuts, particularly adjacent to barbed wire or thorny plants… .

E.25. It is submitted that such widths cannot be reduced on the basis that the bridleway is not physically constrained, if the effect is that, in order to maintain ‘safe and convenient passage’, a user may need to trespass off the extent of the highway.

E.26. Would a public path along a farm track demand a greater safe width than one following a discrete alignment solely for path users? For example, if a horse rider met a combine harvester using the track, the rider might need the whole of the true width (and more) in order to enable safe passage. Even a horse rider passing a motor car might demand 5 metres in width to enable passage

E.27. But note that, where a public path becomes subject to use by vehicles after the cut-off date, the SCW will be what was necessary at the cut-off date, and cannot be influenced by subsequent change of circumstances (unless perhaps those changed circumstances reasonably were foreseeable at the cut-off date — for example, if planning permission had been granted for development). Similarly, if a bridleway is seldom used by horse riders or cyclists at the cut-off date, but owing to local development, becomes frequently used by both some years later, no account can be taken of the increase in use in determining what was a SCW at the cut-off date.

E.28. The likelihood is that the proposed saving for a SCW would demand specific consideration in relation to every public path subject to the EEW, even if, in the majority of cases, the outcome ought to be consistent between public paths of the same status and context.

E.29. But the identification of the safe width will remain unknown until some subsequent cause for determination (such as the confirmation of a definitive map modification order, or a successful prosecution for partial obstruction). Until such a determination is made, the legal width of a way affected by the EEW can be only a matter of conjecture: it will be a width which is not less than the recorded width, and not greater than the true width, and it will be a width which is sufficient for ‘safe and convenient passage’.

E.30. It may be assumed that the EEW will lead to a number of applications for definitive map modification orders to record the amended widths where the EEW is known to have had effect, although land owners and occupiers may generally be content to rely on the recorded width shown in the definitive statement. Thus it seems more likely that such applications will be sought by path users, and their representative organisations.

E.31. Because the EEW was not contemplated during passage of the CROW Bill, the regulatory impact assessment does not consider or quantify its effect. It is submitted that the regulatory impact assessment for implementing legislation should do so, taking into account any proposed savings.

E.32. In practice, the effect of the EEW taken with the saving for a SCW will be to substitute for what is often either known (e.g. a width stated in an inclosure award) or unrecorded but discoverable evidence (e.g. the width of a green lane between walls), with a value which is uncertain (the width recorded in the definitive statement, together with the SCW). Given the likely scale of the EEW, that substituted width may never be determined and recorded.

Bespoke savings

E.33. Further provision could be made to provide savings for bespoke contexts, including to address some of the issues noted above. A saving provision could diminish or exclude the operation of the EEW in specified circumstances.

E.34. Such provision would need to operate in precisely identifiable circumstances, and moreover, in circumstances which might need to be identified as having subsisted at the cut-off date, if the legal width of the way is to be determined by a definitive map modification order (or in any other needful situation, such as a planning consent allowing for development either side of the public path) many years later.

E.35. A saving provision which expressly addresses the context of Church Lane, or similar contexts, might provide that less of the paved footway is extinguished, and more of the grassy verge. But such provision would need to be tailored to that particular context, and would raise potential difficulties — for example, what sort of surface would quality, how wide, for what distance (compared to the path as a whole), and in what state of repair?

E.36. A saving provision theoretically could address a context where the beaten bath were eccentrically positioned within the true width of the way. But it is hard to conceive how such provision satisfactorily could address a context which may be ephemeral. It is not unusual, for example, for the beaten path within a wider corridor (for example, an overgrown green lane) to vary over time, the alignment being affected by, for example, private vehicular use, fallen trees, highway authority vegetation cutting activity and encroachments. If the part of the way to be subject to the EEW were to be defined by that part in use at the cut-off date, it is not obvious how that part could be identified many years later for the purposes of a definitive map modification order.

F. Grant of private rights

F.1. It has been proposed that, where a way is extinguished on the cut-off date, provision should be made to preserve a private right of way, where13:

immediately before that extinguishment, the exercise of the right of way—

(a) is reasonably necessary to enable a person with an interest in land to obtain access to it; or

(b) would have been reasonably necessary to enable that person to obtain access to a part of that land if the person had an interest in that part only.

F.2. It is not clear whether such provision would apply in the context of the EEW.

F.3. Where a landowner, as frontager, owns land adjoining a public path subject to the EEW, and the frontager’s title may be presumed (or is recorded as) extending to the centre line of the path,14 the frontager is entitled to access to the path from that land.15 The EEW will have no effect on the frontager’s access to the path, because the frontager owns the land at the side of the path over which is extinguished the public right of way. Any difficulties which might conceivably arise in relation to a tenancy of the frontager are not explored here.

F.4. But what if the frontager does not own the land comprised in the public path itself — if, for example, the land comprised in a public path is registered as belonging to another party? The EEW will create a thin ‘ransom strip’ between the frontager’s land and the public path — perhaps no more than a few centimetres wide.

F.5. In such a case, it may be that provision to preserve a private right of way may secure the frontager’s access to the public path. If so, it is not clear how it would operate. In relation to a public path subject to extinguishment on the cut-off date, it is clear that the provision operates to preserve a private right of way over the extinguished public right of way. But in relation to the ransom strip, does the frontager acquire a private right of way over the entirety of the ransom strip, or only over enough of it to maintain convenient access? If the latter, where is the right of way granted in relation to the length of ransom strip? Would it lie opposite to an existing gate giving (former) access onto the public path, and if so, how wide? What if (prior to the cut-off date) there were two or more such gates? What if there were no physical barrier, and the frontager took access wherever it happened to be convenient?

F.6. If a private right of way were granted, and applies along the length of the ransom strip, then the owner of that ransom strip (and of the public path) potentially is placed in a still more inflexible place than were it still subject to a public right of way, because any variation to the private right is a matter for negotiation with the frontager, and not subject to variation by a public path order.

F.7. Not all requirements to preserve access over the ‘ransom strip’ would be satisfied by the conferral of a private right. For example, if the public path abuts a public park or other public place, but the whole width of the public path lies in separate hands to the public place, any EEW is likely to sever access from the public path to the public place. It is not clear that a private right of way, such as is proposed to be conferred on the owner of the public place (for example, the local authority), would be sufficient to enable general public access over it.

G. Other exceptions to extinguishment

G.1. The EEW may be excluded if the right of way is otherwise excepted from extinguishment. For example, it is expected that ways recorded on the list of streets16 will be excepted from extinguishment.17 Thus it might be expected that ways recorded on the list of streets (but with a width less than the true width specified in the definitive statement) will also be excluded from the EEW. But if so, the provision will lack coherence: why should the EEW have effect on a way with a width less than the true width specified in the definitive statement, but not if the way also appears in the list of streets — which itself contains no specification of width?

G.2. Similarly, consideration is being given to whether ways in urban areas should be excepted from extinguishment. It might then be expected that such ways will also be excluded from the EEW.

G.3. It is further expected that historical ways which remain, broadly speaking, in regular use will also be excepted from extinguishment.18 It is unclear whether such an exception could be applied to any right of way otherwise subject to the EEW. If, potentially, it could, it would raise the question of whether, and if so, what evidence would be required to show that the full, or some lesser, part of the true width of a right of way, beyond the width recorded in the definitive statement, remained in regular use at the cut-off date.

G.4. For example, where the full width comprises a metalled road, it might be inevitable that the full width remains in regular use, and would be excepted from extinguishment. But what if part of the road were obstructed by a shipping container for a period of some years prior to the cut-off date — would that be sufficient to prevent the exception arising, and if so, over what distance (apart from the length of the container itself)?

G.5. In relation to Church Lane (see Illustration 3 below), what evidence would be required or could be adduced that the grassy verge remained in regular use (as opposed to the paved footway)? Would such evidence be required in relation to every part of the grassy verge, so that the right of way over parts might be found to have been extinguished (for want of evidence of regular use), and that over other parts might not?

G.6. Church Walk in Thames Ditton (Illustration 3 above) is designated Esher footpath 19. The definitive statement records a width of 14 feet.19 Parts of the footpath exceed 14 feet in width between (typically) the picket fences associated with dwellings with frontage along the footpath. It may be that the EEW will be excluded in its operation here because of any of the above exceptions to extinguishment (but it is not obvious how any width additional to 14 feet would be necessary to a SCW). Assuming that it is not excluded, the EEW will enable frontagers to move forward their picket fences by one half of the extent of the EEW.

H. Conclusion

H.1. It is suggested that:

- The EEW, so far as it has effect, is an unintended consequence of the legislation.

- The EEW was unknown until recently, and still remains generally unknown.

- No steps have been taken to preserve public paths from the EEW, by seeking to record the true widths of EEW-candidate public paths, because there has been no understanding of any need to do so, and the identification of EEW-candidate paths is beyond the capacity and resources of the public, user organisations and surveying authorities.

H.2. The EEW, if given effect, even with a saving for SCW, will have a widespread effect on public paths so as to reduce width to a SCW, where the EEW confers no real benefit on any person — such as in relation to enclosed tracks and green lanes. But it will also enable landowners to enclose land from public paths which is recognisably ‘public’.

H.3. Notwithstanding savings, the EEW will have numerous unintended consequences, such as extinguishing the very part of a wide public path which is kept clear for public use, or causing a public bench to be isolated on now private land.

H.4. These consequences are likely in some cases to be high profile, and reflect poorly on Government, local authorities, and the landowners concerned.

H.5. The outcome of the EEW will not create greater certainty about the width of public paths, but less. Many public paths eligible for the EEW will acquire an undefined width which is known to be of or less than the true width, but of or more than the width given in the definitive statement. That width will be incapable of determination without costly public proceedings.

H.6. Therefore, it is submitted that:

- If the EEW is indeed a consequence of s.53, it should be excluded from operation.

- If the EEW is not excluded from operation, its impact will be so widespread, arbitrary and unfathomable that, far from delivering greater certainty about the extent of public rights of way, it will diminish and harm such certainty.

————————

Footnotes

1 Memo of the West Riding County Engineer and Surveyor, addressed to the county clerk, of 2 December 1954.

2 Failure to record rights under NPACA 1949 in the West Riding, National Federation of Bridleway Associations Paper 2, March 2007. The figures do not include Area 4 (Barnsley, Royton etc.). The modifications were not required to be advertised.

3 R (on the application of Edison First Power Ltd) v Central Valulation Officer, [2003] UKHL 20 per Lord Millett at para.117.

4 Hanlon v Law Society [1981] AC 124

5 Heading to s.53.

6 S.54(2)(d) provides that an historical right of way is not extinguished if part of that way was stopped up after 1949 as respects only part of its width. It therefore is not an extinguishing provision, but a saving provision as respects the entire way.

7 Stepping Forward, 25 March 2010

8 The author worked in Defra (and its predecessor, DETR) between 1998 and 2003 on Part I of the 2000 Act, and had regular contact and discussions with those involved in Part II.

9 The question of widths and the potential impact of CRoW Section 53 extinguishment at the 2026 cut-off date.

10 The Excepted Highways and Rights of Way (England) [draft] Regulations, product 4b exceptions version_5b 180318, rr.5 and 6.

11 Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006, s.67 (see the exception to extinguishment specified in subs.(2)(a)).

12 BHS guidance on Dimensions for width, area and height

13 The Excepted Highways and Rights of Way (England) [draft] Regulations, product 4b exceptions version_5b 180318, r.9. R.9 is modelled on the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006, s.67(5)–(7).

14 i.e. applying the presumption ad medium filum.

15 Marshall v Blackpool Corporation [1935] AC 16.

16 Held under s.36(6) of the Highways Act 1980.

17 The position remains unclear in relation to a way which is an unrecorded bridleway or restricted byway over a recorded footpath or bridleway (respectively) which is also recorded in the list of streets.

18 The proposed exception would apply to a footpath or bridleway which has been in frequent and consistent use by the public, and to an extent congruent with its status, throughout a full period of five years ending with the cut-off date. The Excepted Highways and Rights of Way (England) [draft] Regulations, product 4b exceptions version_5b 180318, rr.3 and 4.

19 The statement records an opening width of 14 feet, but is not clear whether that width applies throughout.

Hi Hugh, Fascinating article and shows how easily it is to write something simple at a desk without any consideration of the implementation in the real world.

I had a question raised by a motorcycle rider. “If the wall to wall width is 12 foot and the FP has a 3 foot width then what in law prevents me riding on the other 10 feet?” From everything I have read I think he can. It technically becomes a trespass issue?

And secondly, where dual status (LOS and DM) exists, surely NERC Pt6,S67 2b allows him to ride on the footpath anyway whether or not the vehicular right is actually recorded. Your thoughts would, as always, be valued! Mike

Ha ha! 12 foot minus 3 equals 9! Sorry!

Hi Mike. Do you mean a 12ft footpath which is recorded in the definitive map and statement as 3ft? The statement is conclusive as to the status of the width recorded, but not, I think, as to what is not recorded. If the footpath truly is 12ft wide, and there is evidence to support that conclusion (e.g. an inclosure award or a diversion order, or any good historical or user evidence), then riding a motor cycle on any part of the 12ft footpath will be an offence under s.34(1)(b) of the Road Traffic Act 1988. Under subs.(2) of s.34, a way recorded in the definitive map and statement as a footpath is presumed to be such unless the contrary is proved (though of course, this throws up the question of whether subs.(2) applies to the bit which arguably isn’t shown in the definitive map and statement, because it’s outside the recorded width).

In any case, even if I were wrong about that, there may also be the practical challenge in identifying what exactly is the 3ft recorded in the definitive statement and whether the motorcyclist had been on or off the definitive width along the whole length of the footpath — these are questions of fact, and I do not know where the burden of proof would lie.

On your second question, if a public carriage road were shown in the list of streets on 2 May 2006 (in England) and also on the definitive map and statement as, say, a footpath, any MPV rights would have been extinguished unless one of the other exceptions in subs.(2) (i.e. paras.(a) and (c) to (e)) applied.

Many thanks as usual for the prompt reply. I get the feeling that in the case of being challenged for riding in a 12 foot LOS lane with a 3 foot stated DMS width, it is a case that probably wouldnt be pursued as it is just too complex!

Have a good Christmas

Mike

Surely ‘safe and convenient passage’ must include provision for users to pass safely? Apart from obvious widths being necessary for horses to get past each other (including riding and leading), as a woman, I would feel very uncomfortable at being forced to pass close to a man on some of the illustrated routes above, particularly those with housing either side, if the fences were moved closer together, and during evening or early morning in limited daylight.

Surely it must. But how much is it? And how is it to be determined in each and every case? And at what cost? And with what purpose? And so on… .

I wonder how you think women, who have PROW claimed to go through their own gardens and are subjected to ANY strange person on their property at ANY time of night or day feel!!!!!!!!!

What’s this got to do with the extinguishing effect on widths?

A reply to Joanna roseff, who puts her comfort and safety first but is happy to claim bridleways which threaten the safety and comfort of others.

See my blog on Restoring the Record in East Kent, at the paragraph which begins, ‘I was asked by a friend…’.

Contrary to the aphorism, an Englishman’s home is not his castle. Owning land comes with obligations as well as benefits. If a claimed right of way really will intrude, it’s open to the landowner to pursue a diversion.