In 2014, Allen Lambert, an employee of the Stody Estate in Norfolk, was convicted of offences under s.1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, involving the poisoning of raptors. The offences are not in doubt. However, a recent High Court case, R (on the application of Stody Estate Ltd) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, has questioned the extent of penalties which may be imposed for breaches of cross compliance under the Common Agricultural Policy.

The Stody Estate was previously farmed by the late Ian MacNicol, a former president of the Country Land and Business Association (it was the plain Country Landowners’ Association in those days, but is still known as the CLA). The late Michael Meacher, the then Minister for the Environment, was invited by MacNicol to visit his estate in the late 1990s, in the months running up to the expected Government decision on whether to pursue a statutory right of greater access to the countryside: MacNicol wanted to show the Minister that landowners (or at least, some landowners) were already providing additional access voluntarily. The Stody Estate at that time had entered into an agri-environment scheme which included additional, permissive, paths on the estate, in return for payments per unit length of path (some permissive access endures). At that time, I was working in the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, and accompanied the Minister. I think it was our first ‘outing’ with him. We thought he’d left it a bit tight arriving at the platform at Liverpool Street station with about three minutes until departure — but he abruptly turned around and went off to buy a coffee. He still made it. He rather enjoyed winding up officials. During the visit, as us ‘suits’ congregated at the edge of a cultivated field, contemplating the permissive path along the edge, a jogger fortuitously passed us by (proving, unlike some agri-environment access, that this facility was valued by local people), did a classic double take, jogged back, and shook Meacher’s hand, proclaiming himself a great fan. Meacher loved that, as any politician would. Later, as we careered in an estate Land Rover over a pleasant permanent pasture reaching down to a brook, the estate manager (Meacher was closeted with the president in another vehicle) told us of the valuable wildlife, and confided that this site was incompatible with public access. Presumably, otters had nothing against Land Rovers though. (To be fair, greater access with dogs might be another matter.)

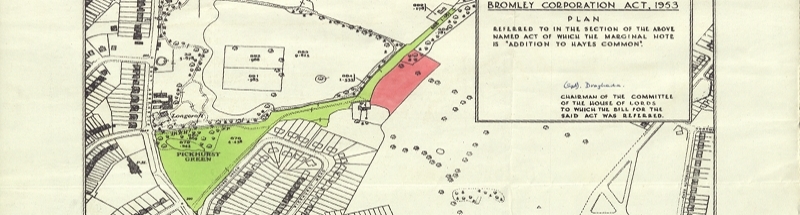

|

| Permissive access on the Stody estate, Photo © Evelyn Simak cc-by-sa |

But back to the present. In the case before the court, the judge started off on the wrong foot. She was poorly briefed by counsel on the purpose of direct payments: she says (para.1), ‘after 2003 [the scheme] changed to one of incentivising conservation: payments were directed to the preservation of the environment, wildlife and habitats.’ Well, if that’s true then, to use the words of one former assistant secretary in charge of the scheme, when challenged on this point in a stakeholder meeting, for €3.5bn per annum, ‘it’s a bloody expensive environmental scheme.’ The truth, of course, is that it’s not an environmental scheme, but a farming subsidy scheme with some environmental dressing.

Under the direct payments scheme, claimants (i.e. farmers who claim subsidy under the Common Agricultural Policy, meaning nearly all) must subscribe to cross compliance, which is a roll call of most of the sectorally-specific statutory obligations under which farmers operate (such as observing the testing regime for tuberculosis in cattle, keeping rights of way unobstructed, and yes, killing of wildlife contrary to s.1 of the 1981 Act). It will be observed that statutory obligations are just that — they must be adhered to regardless of cross compliance, or subsidy, and breaches can usually be enforced through prosecution or, in some cases, civil remedies. But cross compliance theoretically gives the enforcing agencies added heft, because a breach may also, or alternatively, be acted upon by deducting penalties from direct payments. In practice, it is usually ‘alternatively’, if at all, because the capabilities of the enforcing agencies have been undermined by a decade of cuts, and Ministerial antipathy to farm inspections. Indeed, as fewer than one per cent of claimants are inspected each year for cross compliance, it might be imagined that the deterrence effect even of cross compliance ought to be minimal.

Where a breach arises from negligence, the penalties are typically a small percentage of the annual subsidy — perhaps three per cent (although three per cent of a payment exceeding £1m on a large estate of say 5,000ha is still quite a large penalty. Stody is around 1,700ha). But as the court explains in the judgment, where the breach is ‘committed intentionally by the farmer’, the penalty may be raised as high as the annual value of the subsidy itself. That is what happened in the Stody case: a penalty of 55% was imposed.

There was a further step involved in the Stody case, before it reached the court. The estate challenged the penalty, and in due course, appealed to the Minister. The Minister is advised by a panel, who hear the appellant, and report to the Minister with their recommendation. The panel is lay, the members are mainly from the agricultural community, and the secretary is an official but not a lawyer. It may be seen that this is not a structure which is likely to inspire great confidence in the wisdom of the panel’s decisions, although, if properly briefed (which the panel may not be), and effectively chaired, the panel is capable of acting as a fact-finding tribunal. But it has little knowledge of the law, and may not be briefed on the legal questions which may arise in a case. In theory, this gap can be filled by officials’ covering submission on the panel’s report to the Minister, but by then, it is too late to revisit or probe for any missing or unsatisfactory issues of fact. It may also be noted that, in practice, the decision on an appeal really is taken by a Minister. This is not a legal requirement — almost every decision of the Secretary of State may be taken by officials acting on the Secretary of State’s behalf — but one desired by Ministers (and by farmers). It contrasts with, say, decisions taken on behalf of the Secretary of State in relation to works on common land, where even the most significant determinations are made by officials or inspectors. But if a farmer appeals a £200 penalty, Ministers decide.

In the Stody case, the panel recommended a reduction in the penalty of 75% imposed by the Rural Payments Agency, and the Minister agreed. It was the decision nonetheless to impose a hefty penalty of 55% which was challenged by way of judicial review.

The court (Mrs Justice May DBE) had to wrestle with the question of responsibility for the poisoning. Undoubtedly, Mr Lambert was employed by the estate when he committed the offences. What was in question was whether the poisoning could be held to have been ‘committed intentionally by the farmer’ contrary to the relevant EU regulation. In this case, the Stody estate is a limited company, which employed Mr Lambert (one assumes that it no longer does). There is no evidence that the directing mind of the company (Charles MacNicol is currently the Managing Director) knew what was going on. It is sometimes said, in relation to poisoning done by gamekeepers, that a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy is in place, but again, there is no suggestion of that here.

The court was guided by the decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Dutch Van der Ham case, where a penalty had been imposed on a farmer who had contracted operations to a third party. In that case, the European Court concluded, ‘that, in the event of an infringement of the requirements of cross-compliance by a third party who carries out work on the instructions of a beneficiary of aid, the beneficiary may be held responsible for the infringement if he acted intentionally or negligently as a result of the choice or the monitoring of the third party or the instructions given to him, independently of the intentional or negligent nature of the conduct of the third party.’ The opinion of the Advocate General was found by the court to be helpful: ‘a non-compliance is to be penalised only on the basis of the personal responsibility of the aid beneficiary, but that he need not have committed the non-compliance in person.’

That was all very well, but the Stody case related to acts done by an employee, not by a contractor. PannageMan is not a lawyer, and does not wish to research the full gamut of corporate and employment law, but he recalls a principle whereby an employer is liable for the actions of employees unless it is determined that those actions were so contrary to what was required and expected of the employee that the employee must have been off on a ‘frolic of his own’. Whatever, the court chose to chart a different course. It was unpersuaded by counsel for the Secretary of State that the European Court’s decisions in relation to competition law had treated the decisions of employees as binding the employer (para.35): ‘competition law operates as a deterrent whereas the primary purpose of the SPS is to incentivise, to encourage farmers to conserve wildlife and the environment.’ Well, hardly — and even less so if offences against the environment are to attract only a trivial and infrequent sanction under the scheme.

Equally, the court rejected a fairly heroic intervention from counsel for the National Farmers’ Union (which obtained permission from the court to intervene: perhaps the Stody estate was backed by the CLA instead) that, under the EU regulation, it was necessary that a breach was committed by the farmer him, her or itself — and in relation to the claimant company, the Union suggested that meant the managing director, Mr MacNicol, or perhaps, but only perhaps, his estate manager.

But the court did find ‘that there is no uniform understanding across Member States of the distinction between employees and independent contractors’, and the principles of the Van der Ham case could not be confined to farms using contractors. A farmer, for the purposes of the direct payments regulations, did not mean any or every employee. Mr Lambert’s activities could not, ‘without more’, satisfy ‘the requirement in Article 23 that cross-compliance breaches be “the result of an act or omission directly attributable to the farmer”.’ The Minister’s decision to impose penalties was quashed.

The judgment is at first worrying, but perhaps also understandable. Worrying, because it appears at first blush to let farmers off the hook for the deeds of their employees (or indeed, anyone else other than the directing mind of the business). That seems to offer a ‘get out of jail free’ card for any breach — ‘I didn’t do it, it was my farm worker, I told him not to do it’. But as the judge points out, in Van der Ham, the European Court did not give a farmer immunity for the actions of a contractor: it said (para.50, quoted at para.21 of the judgment): ‘In such a case, even if the beneficiary of aid’s own conduct is not directly the cause of that non-compliance, it may be the cause through the choice of the third party, the monitoring of the third party or the instructions given to the third party.’ In other words, the farmer may still be held liable, but there must be some evidence that the conduct of the farmer is intentional or negligent, perhaps in failing to properly brief an employee or contractor (e.g. as to environmental features protected by cross compliance, or failing to take steps to follow up allegations of raptor poisoning). In practice, where the penalty imposed is at the lower end of the scale at around three per cent, it may not be too difficult to find that the farmer acted negligently by failing to properly regulate the activities of those working on the farm, whatever their relationship to the farmer. After all, if you ask a contractor to harrow a field, but fail to point out that there’s a footpath across it which you want reinstated, it’s not hard to conclude that you’ve been negligent. But it’s quite another thing to demonstrate that the intention of an employee is the intention of the employer.

This appears to shift the burden onto the Secretary of State (or at least, the Rural Payments Agency) to establish intention or negligence. But not so fast. The judge (para.35) notes: ‘the approach of the Court in Van der Ham to an evidential presumption adopted by the Dutch authorities: the Court had no objection, provided that an opportunity was given to the farmer to rebut the presumption (see the discussion at paras 38–42 of the Van der Ham decision).’ So the Agency can presume the farmer to be responsible, but must give the farmer an opportunity to challenge the presumption. And that is exactly what the appeal panel should be doing — if only it were properly briefed. Instead, it approached the Stody case on the assumption that the estate was inevitably liable for the wrongs of its employees, and merely had to relay any mitigation to the Minister. It will surely now hear the claimant again, and form a view as to whether the estate had acted intentionally or negligently in the matter of the raptor poisoning.

Alternatively, of course, the Secretary of State may appeal (there is no suggestion in the report of a referral to the European Court). But I suspect that is unlikely, as Ministers may well be content with a decision which constrains their power to impose penalties. Farmers will like that.